SingHealth Institutions will NEVER ask you to transfer money over a call. If in doubt, call the 24/7 ScamShield helpline at 1799, or visit the ScamShield website at www.scamshield.gov.sg.

While coping with the neurodegenerative disease ALS can be an arduous journey, supporting patients to retain a sense of control and independence in its early stages is vital to an enhanced quality of life.

Mr Philip Yap was having trouble adjusting screws. The engineer in the semiconductor industry found his fingers fumbling with the everyday tools of his day job.

It was not the only sign that something was amiss. His speech had also begun to slow. He brought his worries to a check-up at the hospital, where he underwent physical examinations, assessments of symptoms, and electrodiagnostic studies to measure the damage to his muscles and nerves. The signs pointed towards a diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), more commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease in the United States.

ALS falls under the category of Motor

Neuron Disease (MND), a group of

neurological conditions that affect the

neurons, or nerves, responsible

for movement. In ALS, the

degeneration of these motor

neurons leads to progressive

muscle weakness, stiffness

in limbs and difficulties with

chewing, swallowing and

breathing, culminating in death.

According to Associate Professor Josiah Chai (pictured, above), Head and Senior Consultant, Department of Neurology, National Neuroscience Institute (NNI) at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, most patients likely have a genetic predisposition to ALS, although genetics cannot fully account for the occurrence of this condition. Other factors, including unknown environmental ones, may also play a part. While genetic tests for ALS are available, they are usually offered to younger patients (under 50 years old) or those who have a family history of the condition.

“There is much more that needs to be understood about ALS,” said Assoc Prof Chai, who explained that there are two types of ALS. The first type runs in families and is caused by “a single faulty gene” typically found in younger patients. The second type is unrelated to familial medical histories and is thought to strike at random, commonly occurring in people aged 50 years and older. Currently, around 250–300 people are living with ALS in Singapore, with 30–40 cases diagnosed at NNI each year. Due to the ageing population, this number is expected to rise over the next few decades.

“ALS is now believed to be a multi-step disease, similar to cancer,” said Assoc Prof Chai, who also serves as a member of the advisory panel at the Motor Neurone Disease Association Singapore. But unlike cancer, for which treatments could lead to remission, there is no cure for ALS. Medications merely slow its progression, leaving the average life expectancy to between three and five years, although approximately 10 per cent of patients survive beyond that. Famously, the late influential theoretical physicist Professor Stephen Hawking lived with ALS for 55 years.

While there are drugs that address ALS, the mainstay of treatment is supportive care and regular monitoring at a specialist ALS clinic to prevent problems before they occur. This multidisciplinary approach involves the collaborative input of community and specialist teams of doctors, nurses, dietician, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, medical social workers and respiratory therapists to best manage the unique needs of each patient. In the advanced stages, some patients may opt for mechanical ventilation to support their breathing, while others may choose palliative care.

“This is often a challenging diagnosis,” Assoc Prof Chai said. “One common question is, ‘How long do I have to live?’” Patients and their caregivers can experience anxiety and depression over the uncertainty of the future and quality of life. This makes it crucial to help patients maintain their function and independence as much as possible, especially in the early stages. “Exploring their goals and advance care planning can ensure that a patient’s values and care preferences are respected throughout their illness and when they pass on,” said Assoc Prof Chai, who added that patients who adapt to live with their condition, receive robust social support and maintain a positive outlook typically experience better outcomes.

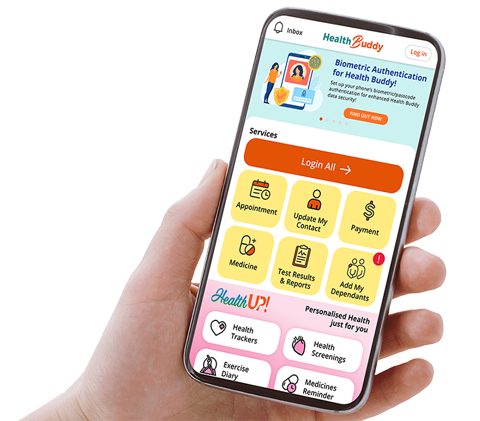

Mr Yap’s journey as an ALS patient reflects this sentiment. “I am thankful to be living in the 21st century, where I can manage my life through online shopping, banking and connecting with friends and family through technology,” he said. To cope with the condition, he has also implemented smart home systems to maintain a degree of independence in daily living. Currently in the eighth year of his diagnosis, Mr Yap offered a message of hope to fellow ALS patients: “Like mine, your life may have worsened significantly, but please don’t give up. Live your life to the fullest, even with ALS. Our stories are testament to the human spirit and how determination and resilience can overcome even the most challenging circumstances.”

Get the latest updates about Singapore Health in your mailbox! Click here to subscribe.

Keep Healthy With

© 2025 SingHealth Group. All Rights Reserved.