By Akshita Nanda

Visual aids, predictive text and apps can help those with aphasia.

Madam Suphattra Taengyotha likes meeting new people. She smiles at this journalist and presses a button on her tablet. An artificial voice asks: “How are you?”

The former cook, who turns 62 in 2026 and prefers to be known as Madam Noi, had a stroke just over three years ago. She cannot speak clearly, but can read and spell.

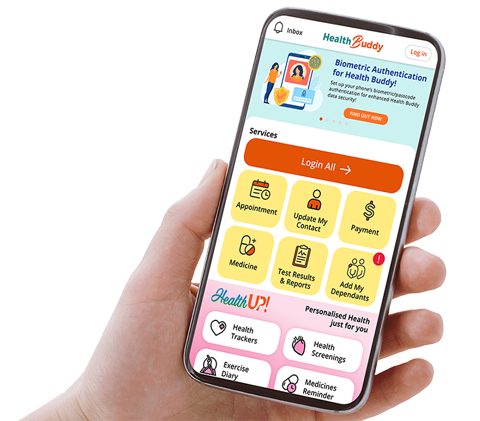

By slowly pressing keys and buttons on her augmentative and alternative communication device, or AAC, she can ask or answer simple questions and make her wishes known.

Madam Noi has aphasia, a language disorder that can affect a person’s ability to speak, to process what he or she listens to, and his or her ability to read or write.

Aphasia can happen when the brain is damaged by traumatic injury or medical conditions. A brain aneurysm led Game Of Thrones (2011 to 2019) actress Emilia Clarke to develop aphasia. American actor Bruce Willis' aphasia is a result of degeneration of the frontotemporal lobe.

In Madam Noi’s case, the stroke affected the parts of her brain that control speech and communication. The Singaporean attends speech therapy twice a week at the Jurong Point branch of Stroke Support Station (S3). She practises spelling out names of tools used by the speech therapist and choosing the correct pre-recorded voice message to answer questions.

Speech therapists tell The Straits Times that everyone’s experience with aphasia is different.

Some, like Madam Noi, cannot speak. Others may be able to speak, but not articulate their thoughts clearly. Some also have difficulty comprehending what they listen to or read.

Many people with aphasia find it easier to process information through images, which is why a pictorial communication booklet was released in October 2025 by the Stroke Services Improvement (SSI) team, appointed by the Ministry of Health.

The booklet is available for download in English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil, and copies have been distributed to public hospitals for use.

The images within can help people with aphasia indicate their preferred foods, or current needs, such as to wash their face or use the toilet.

Madam Lim, a stroke survivor who wants to be known by only her surname, says a similar set of images was helpful when she was in hospital after a stroke in 2021. She could point at pictures, though she could not express her desires in words.

“I couldn’t say what I wanted. I couldn’t move and I couldn’t express myself,” recalls the former nurse. Today, the 54-year-old speaks slowly and with long pauses between words.

Like many others with aphasia, she prefers to send messages on her mobile phone or write e-mails.

The predictive text function in her devices makes up for gaps in her thinking.

“When I look at the phone keyboard, then I know the word,” she says.

Communication Woes

Aphasia is often an invisible disability.

Mr Henry Gui had a stroke in August 2025. He can move without difficulty, but cannot always speak clearly. While he can recognise words, pronouncing them is hard.

When he wants to order prata at the hawker centre, he ends up saying “lata”. The stallholder does not understand, and confusion leads to irritation on both sides.

The retired civil servant, 66, now starts a conversation by being open about his condition. “Before I talk to a person, I say: ‘Please bear with me,’” he says. “The way I talk, people might think I’m making fun of them. But now, they understand and adjust.”

Ms Irene Tan, who is in her early 50s, had a stroke in September 2022 that left her with aphasia. She answered ST’s questions via e-mail, explaining that she prefers written communication to speech.

Ms Tan, who used to work in brand and marketing communications, writes: “My thoughts are clear, but the words don’t always come out. I struggle with wordfinding, sometimes substitute the wrong words, mix up my speech or produce sentences that don’t make sense.”

Like Mr Gui, she finds it challenging to order food at the hawker centre. Apart from her difficulties with speaking, the noise level makes it harder for her to be heard.

She writes: “It’s frustrating because people often misunderstand aphasia. The problem is with language, not intelligence.”

Then there is the converse – having people think that they are being mocked when a person with aphasia speaks.

“Many people with aphasia look perfectly healthy, so others misunderstand them,” she writes. “Some think they are joking or not serious.”

Like Madam Lim, she prefers messaging on her cellphone to making phone calls. When it comes to banking and other administrative tasks, she prefers interacting with chatbots to talking to a customer service officer.

“I want everything done without talking,” she writes.

Battling Isolation

Communication is essential for relationships. When one party has problems expressing himself or herself, or understanding the other, even intimate ties can fray under the pressure.

Madam Lim recalls quarrelling often with her husband in the earlier stages of her recovery, when she had more difficulty speaking. “I would cry and get angry,” she says. “He would scold me, but I couldn’t scold him back. I was very angry.”

She is married to a doctor, and they have a son below the age of 10.

Other members of the family also had little idea how to communicate with someone with aphasia.

Speech therapist Evelyn Khoo says people with aphasia are often devastated by their inability to communicate their needs and feelings. Their caregivers are frustrated too.

Apart from feeling neglected at home, people with aphasia also end up feeling socially isolated.

To combat this, Ms Khoo trialled not-for-profit organisation Aphasia SG in 2018, incorporating it as a company limited by guarantee in 2019.

Aphasia SG organises workshops for public speaking and supports a choir whose members have aphasia. Music and rhythm help bypass the injured areas of the brain, allowing people with aphasia to pronounce words with greater ease.

The flagship event is the monthly Chit Chat Cafe for people with aphasia and their caregivers to meet and interact.

It is held online and offline, with speech therapists and volunteers supporting participants. Drawing and using phones or other communication tools are encouraged.

Ms Khoo says: “We want them to have a safe space to practise talking. They could fumble and make mistakes, but everyone there knows what aphasia is.”

Madam Lim’s family has learnt to give her time to talk and to adjust to her pace. Interacting more with people is helping her improve as well. People with aphasia benefit from practising to improve their areas of weakness, whether it is speech, comprehension or writing.

At S3, Mr Gui alternates sessions in Chinese and English, filling in blank words and trying to identify errors in written passages.

“In August last year, I couldn’t even text people correctly,” he says with a laugh. “Now, I can tell the therapist which words are wrong. Before, it was a disaster.”

Tools, Practice and Patience

Various tools can be used to bridge communication gaps. Madam Noi uses an augmentative and alternative communication device, while Madam Lim relies on predictive text and apps. The SSI pictorial booklet can help caregivers and people with aphasia identify preferred foods or desired activities.

Associate Professor Deidre De Silva is chair of the SSI team and says the booklet was designed specifically for people with language difficulties. It was revised multiple times based on feedback from patients, caregivers, nurses and speech therapists.

“This booklet aims to help people with aphasia to express themselves with less difficulty with a tool that is culturally relevant and in the national languages,” adds Dr De Silva, who is also a senior consultant at the National Neuroscience Institute’s department of neurology.

“It is very frustrating for people with aphasia to not be able to express themselves, to be misunderstood, sometimes ignored and not given a choice because of their communication impairment.”

Speech therapist Sajlia Jalil says it helps people with aphasia to have trusted communication partners who understand their abilities and difficulties.

“Communication partners – family members, friends, colleagues and caregivers – play a crucial role in helping a person with aphasia communicate confidently and participate fully in everyday life,” says Dr Sajlia, who is head of speech therapy at Woodlands Hospital.

Creating a supportive environment for people with aphasia includes reducing background noise, if possible, and allowing them the time they need to speak or otherwise communicate, she says.

“Avoid finishing their sentences unless they ask for help,” she adds.

Speak in short phrases; ask one question at a time and offer choices (“tea or coffee?”) instead of asking open-ended questions (“what would you like to drink?). All forms of communication should be encouraged, whether spoken words, gestures, pointing, typing or picture-based apps, she says.

Non-verbal communication strategies, such as writing, drawing, pointing to pictures or using gestures can supplement speech and help get the message across clearly.

“Acknowledge and respond to any successful communication,” she adds. For Madam Noi, the AAC helps her communicate with her domestic helper, husband and two grown children.

Before her interview, she painstakingly pre-programmed the device with answers to questions sent in advance.

She tells ST that she has been married for 34 years. She would like one day to regain enough mobility to go back to cooking Thai food, which was both her occupation and her passion.

She presses a button on her AAC and a voice message plays. “Keep believing in yourself,” it says. “You can do it.”

Madam Noi smiles.

E-Resources Related to Aphasia and Stroke

- Download the pictorial communication booklet and other resources for stroke survivors and their caregivers at str.sg/8VrfPG

- Connect with non-profit support group Aphasia SG at aphasia.sg

- Free communication apps for people with aphasia: SmallTalk (on the App store); LetMeTalk (Google Play Store and App Store)

- More resources for stroke survivors and caregivers are available at S3 Stroke Support Station (s3.org.sg) and Singapore National Stroke Association (snsa.org.sg/homesofs2025)

Source: The Straits Times © SPH Media Limited. Permission required for reproduction.