From shrinking bones to sagging skin, experts explain what age does to your face.

Facial ageing occurs at every level, from bone and muscle to fat and skin, and is influenced by both genetics and lifestyle.PHOTOS: ADOBESTOCK, ST GAVIN FOO

I remember the exact moment I realised I was no longer young.

I was 44, walking up an overhead bridge on my way to a sports stadium for a run.

It was late afternoon and the sun was still blazing. For some reason, my left hand was pressing against the inside of my right forearm, scrunching the skin slightly. I looked down and thought, “Wow, when did I start becoming so wrinkled?”

I’d only ever known my underarm skin to be soft, smooth and cushiony. But now it was thin, crepey and lined. Up there on the bridge, with cars whizzing below me and the sun beating down, I had my moment of reckoning: My youth was slipping away.

Since then, I’ve had to come to terms with more signs of ageing. The most troubling has been my face. It’s not just the wrinkles, crinkles and eye bags, but also the slow and steady downward drift of all my features.

My eyebrows have lowered, my eyelids are more hooded, cheeks flatter and longer, mouth more saggy and the jawline? Oh, my jawline has seen better days.“

As we age, everything goes south,” says plastic surgeon Martin Huang, director of MH Plastic Surgery.

A face in the bloom of youth, he explains, is characterised by features such as fullness in the upper cheeks, tautness below that, and a lack of hollowing in the temples.

“The general shape of the face is more triangular, with good definition. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘triangle of youth’,” Dr Huang says.

“Ageing causes tissue volume to gravitate downwards, changing the facial shape to a more rectangular or square appearance with loss of projection.” (It’s true. My once-roundish face seems to have curiously rectangularised in the last decade.)

Facial ageing occurs at every level, from bone and muscle to fat and skin, and is influenced by both genetics and lifestyle.Facial bone structure plays a key role in how you age. People with prominent cheekbones, a strong jawline and a well-defined chin tend to age more slowly because the bony structure provides better support for the overlying soft tissue, Dr Huang says.

Ironically, such features, like a wide, square face, are often considered less desirable when one is young, he adds.

In contrast, those with smaller, less defined bone structures, such as flat cheekbones or a small chin, experience earlier sagging and volume descent as there is less structural support to anchor and maintain the tightness of the overlying skin and soft tissue.

“Actually, a small chin is not good at any age,” he says, “aesthetically as well as from an ageing point of view.”

Adequate bony chin support helps to stretch the skin and soft tissues on either side of the chin, where the jowls tend to occur, and below it, where the double chin occurs, and thus prevent sagging.

Bone shrinkage invariably happens with age, exacerbating skin and soft tissue laxity. Skin and soft tissue quality is also adversely affected by lifestyle factors such as poor sleep, stress, smoking, vaping, excessive alcohol consumption and an unhealthy diet, says Dr Huang.

These habits can accelerate ageing. “So you can have a 40-something individual who looks like they’re in bad shape, and a 60-year-old who looks great,” he adds.

Even stress plays a role, showing on the face as negative expressions such as frowning.

Some people gain facial fullness due to general weight gain, common with the slower metabolism that comes with age. Others see the opposite – fat loss that causes hollowing in various parts of the face.

“From the point of view of the cosmetic appearance of the face, weight gain can actually be better for the face than fat loss. Fat becomes more a friend than an enemy,” Dr Huang adds. That said, this fullness is not identical to the way youthful fat is distributed in the face, as age-related tissue laxity causes fat to prolapse downwards and outwards.

Role of hormones

Hormonal shifts play a role in how you look when you age.

Dr Swee Du Soon, a senior consultant in the department of endocrinology at Singapore General Hospital (SGH), says that menopause typically occurs in women around the ages of 50 to 52, when oestrogen levels fall sharply.

This has several effects on the skin. The production of sebum, the skin’s natural oil, declines, leading to dryness and reduced hydration. Collagen levels also decrease significantly because oestrogen plays a key role in stimulating collagen production. The result? Thinner, more fragile and sagging skin.

Dr Swee says skin collagen content decreases by around 30 per cent during early menopause, followed by 2 per cent per year post-menopause.

For men, hormonal decline is more subtle.

Dr Swee says andropause – male menopause – is a highly variable condition and does not uniformly happen to all men. While a decline in testosterone may begin around the age of 40, this is often a slow process, at 1 per cent per year, and tends not to result in significant deficiency.

Men with significant testosterone deficiency are more likely to be older than 65 and have chronic health conditions. “Accordingly, any change in appearance is generally gradual and less noticeable,” he says.

As for whether there is a hormonal reason some people develop wrinkles earlier, Dr Swee says that while long-term sun exposure is a key cause of skin wrinkling, oestrogen deficiency contributes by reducing skin elasticity. Women who experience early menopause – before age 45 – could develop premature skin ageing and wrinkles.

Dr Ben Ng, a consultant endocrinologist at Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital, says that when a man’s testosterone levels drop, he tends to lose muscle, gain fat especially around the belly and feel less energetic. “These hormonal changes are part of what gives the face and body a more aged look, beyond just wrinkles,” he says.

While hormones influence ageing, genetics, skin type, sun exposure, smoking, sleep and nutrition significantly determine how changes play out, Dr Ng says. “That’s why two people of the same age can look quite different – their hormonal levels, combined with environmental exposures and daily habits, all interact.” A healthy lifestyle remains key to looking your best.

Identity and mortality

Ageing doesn’t just affect how a person looks, it can also deeply challenge one’s sense of identity.

“For some, the process is seen as a natural evolution. For others, especially those whose sense of self is tightly bound to youthfulness or appearance, ageing can be profoundly unsettling,” says Dr Lim Boon Leng, a psychiatrist at Gleneagles Hospital.

He explains that people who tend to be perfectionists, or have experienced past body image traumas, or struggled with self-esteem throughout their lives may be more sensitive to the loss of youthful features.

Comparing yourself with others, especially on social media where pictures are often edited, and constantly seeing perfect or “ageless” looks, can make you feel worse about yourself.

For some, worries about getting older are also connected to bigger questions such as mortality and purpose.

“The physical signs of ageing... are not just cosmetic changes; they are daily reminders of mortality and decline,” Dr Lim says. “This can provoke anxiety in those who have not yet come to terms with the inevitability of death or who have difficulty finding value in themselves outside of productivity and appearance.

”Women face more pressure. In many cultures, a woman’s looks are closely linked to her social value, with youth and attractiveness often influencing how she is perceived in terms of worth and competence, says Dr Lim. “As beauty fades with age, women may feel a loss of visibility, relevance or even value.

”He adds that research shows that women are more likely than men to invest in their appearances well into later life, “making them more vulnerable to psychological distress when those standards become harder to meet”.

Ms Serene Wong, a principal psychologist at SGH, says the connection between fading beauty, self-worth and mental health in women is complex and influenced by both society and personal feelings.

“Women often face disproportionate pressure to maintain a good-looking and youthful appearance, which can lead to increased anxiety and depression as these standards become increasingly difficult to meet with age,” she says. Hormonal changes during menopause – when ageing starts becoming more apparent – can heighten emotions.

Dr Lee Huei Yen, a senior consultant in the department of psychiatry at SGH, says that fretting over one’s ageing appearance is considered “normal” if the feelings are widely relatable, not severe and don’t interfere with daily life or social functioning.

But if a person becomes obsessively preoccupied with perceived flaws that are not noticeable or appear minor to others, engages in repetitive behaviour such as checking the mirror or constantly seeking reassurance, and this affects daily life, it may point to something more serious.

Dr Lim from Gleneagles adds that it is normal for people to feel concerned or even distressed about ageing, especially during transitional periods such as menopause or retirement. “These concerns are often transient and context-specific, surfacing during milestone birthdays, social events, or health scares. They usually do not interfere significantly with daily functioning,” he says.

For those who feel that ageing is making them feel invisible or irrelevant, his advice is to recognise that this experience, while painful, can help you “redefine what makes you visible and significant in the world”.

He adds: “Visibility does not have to come from being admired for looks; it can come from being known for your wisdom, kindness, authenticity or contribution to others. Be a guru, not a beauty.”

Principal psychologist Kevin Roy Beck at SGH says purposeful activities such as volunteering and pursuing your passions can help fight the feeling of being invisible or irrelevant as you age.

Reflecting on whether your negative feelings about ageing stem from actual ageism or are “self-perceived” can shift the focus “from shame to empowerment”, he adds.

Those who are inclined can seek surgical and non-surgical procedures to look better. These include devices, injections and fillers to erase wrinkles and plump the skin.

Dr Huang, the plastic surgeon, challenges the notion that one should “age gracefully” by passively accepting the visible signs of ageing without intervention. “When basically everything is falling apart, how can that be graceful?” he argues.

In today’s context, ageing gracefully means taking care of one’s appearance by maintaining skin health, seeking treatment when needed, and preserving a natural look, he says.

He adds that the stigma around cosmetic enhancement has declined over the years. While people may still hesitate to admit to treatments, it’s more socially accepted now than, say, a decade ago.

That said, invasive surgical procedures like facelifts are less common today because of many advancements in non-invasive methods to lift, tighten and rejuvenate the face.

When I look in the mirror or an old photo of myself, I can’t help but sigh at the ravages of time.

Then again, I also remind myself that how I look today will likely be better than how I’ll look tomorrow, so shouldn’t I appreciate the now instead of mourn what’s gone?

I’ve also come to realise that smiling helps. It doesn’t erase the crow’s feet – in fact, some studies have found that smiling can make you appear older than a neutral expression because facial lines are more visible.

But smiling lifts the lips and cheeks like a natural facelift, and puts a sparkle in the eyes.

It won’t turn back the clock, but a genuine smile brings warmth and friendliness to the face. That, at any age, is always attractive, and something no cosmetic procedure can really replicate.

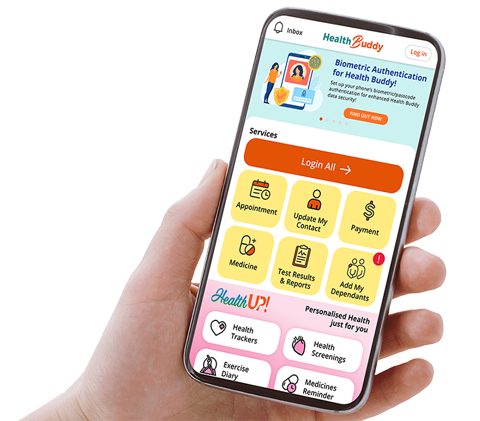

Changing looks

Plastic surgeon Martin Huang on how facial features change with age

1. Facial fat

• The face contains multiple layers of fat and muscle that age differently.

• Superficial fat (just beneath the skin) typically shrinks and sags together with the skin, contributing to skin folds and wrinkles, and drooping of the cheeks and jawline. It can also cause hollowing of different parts of the face, such as the forehead and sides of the cheeks.

• Deep fat (closer to the bone) may also shrink, and tends to prolapse outwards and downwards in the lower cheek, accentuating the appearance of jowls in the lower face. This shrinkage can lead to volume loss and hollow, sunken areas in the temples and around the eyes.

2. Hair

Hair greys and thins, and often starts to turn white, especially after age 50.

3. Eyebrows and eyelids

Eyebrows sag as skin and underlying tissues (muscles and connective tissue) weaken, causing more skin to hang over the upper eyelids.

4. Eyes

• Eye bags form in the lower eyelid when the fat that cushions the eyeball inside the eye socket prolapses, or bulges forward.

• Hollowing under the eyes (tear troughs and malar grooves in the upper cheek) becomes more noticeable, creating a tired, haggard look.

• Eyelid ptosis (drooping of the upper eyelid) results from loosening of the eyelid muscles.

5. Nose

The nasal tip may droop and the nose may appear wider due to weakening nasal cartilage.

6. Lips

Loss of fat and bone around the mouth reduces the support that gives lips their shape and fullness. This makes the red part of the lips (vermillion) less prominent and may cause it to turn inwards. Decreased collagen also leads to thinner lips with more vertical lines.

Other changes

Bone

Bone resorption (shrinkage) occurs mainly in the jaws, chin and eye sockets. This loss of bone reduces support for the skin and soft tissue layers, and causes sagging, wrinkles and a loss of facial definition.

Facial shape

Youthful faces have fullness in the upper cheeks and temples, forming an inverted triangle shape with good definition. Ageing causes volume to shift downwards, changing the facial shape to a more rectangular or square appearance with loss of projection.

Skin and muscle

• Skin thins and loses collagen, which leads to loss of strength and elasticity. It also becomes dehydrated, leading to dryness, rough texture and fragility. Accompanying hormonal changes can lead to uneven pigmentation and exacerbate wrinkles.

• Repeated facial movements like frowning, smiling and puckering of the lips create dynamic wrinkles that can become permanent.

Lower face and jowls

Cheek fat (buccal fat) can descend or protrude, leading to sagging jowls. Combined with volume loss in the jawline, this results in heaviness and sagging in the lower face. Changes in neck fat and increasing skin laxity can further compromise the definition of the jawline.

The Straits Times, Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reproduced with permission

Contributed by