Clin Asst Prof Cherylin Fu

Director, Research & Service Chief @SGH, SingHealth Duke-NUS Pelvic Floor Disorders Centre;

Director, Pelvic Floor Disorders Service & Gastrointestinal Function Unit,

Senior Consultant, Department of Colorectal Surgery, Singapore General Hospital;

Division of Surgery and Surgical Oncology, National Cancer Centre Singapore

A patient’s perception of constipation can be subjective, making it challenging to handle this common problem. As lifestyle changes and first-line medications are the mainstays of treatment, we share how a systematic and clear diagnostic approach can enable effective treatment in the primary care setting while remaining vigilant for “red flag” symptoms that require immediate specialist referral.

INTRODUCTION

Constipation is a very common and often distressing gastrointestinal issue frequently seen in primary care settings. It is more than just in frequent bowel movements; it also involves the quality and pattern of defaecation, meaning individuals can suffer from it even if they have daily bowel movements.

The condition can significantly harm a person’s qualityof life, work productivity and mental well-being. Therefore, it should be taken seriously, even when no underlying physical cause is found.

PREVALENCE OF CONSTIPATION IN SINGAPORE

Understanding the local situation is vital for GPs in Singapore. A community study in Bishan found that chronic constipation affects about 7.3% of adults. This rate is similar to other local and Western studies, indicating a consistent pattern in bowel habits across different populations.

Gender

A key finding is the significant difference between genders. In Singapore, women are much more likely to have chronic constipation, with a prevalence of 11.3%, compared to just 3.6% in men. This aligns with global trends where women’s stools are more often hard and lumpy, as classified by the Bristol Stool Form Scale. Interestingly, the study found that age and ethnicity did not have a major impact on the rates of chronic constipation in Singapore.

Severity of symptoms

A separate survey focused on Singaporean women with the condition revealed that their symptoms are often severe. A large majority of 88% reported straining, and 80% experienced lumpy or hard stools. On average, these women dealt with symptoms for about six to seven months out of the last year.

Self-treatment

Despite the severity, most women (94%) had tried to treat themselves before seeing a doctor, with 80% using laxatives. The reasons for not seeking medical help sooner include feelings of embarrassment about discussing the issue and the belief that constipation is not a real medical problem, or that it would resolve on its own. When they do seek medical advice, GPs and primary care physicians are the most consulted professionals, seen by 77% of these women.

Satisfaction with treatments varied. Fibre supplements received average satisfaction ratings, while laxatives were viewed more favourably, with 65% of users reporting satisfaction. However, common complaints about treatments included ineffectiveness and the long time to take effect.

A striking 97% of the women surveyed expressed a desire for more effective prescription medications.

Managing expectations

This highlights a need for GPs to manage patient expectations about how quickly first-line treatments will work. It is important for doctors to explain that improvement is often gradual and to stress the importance of sticking with the prescribed therapy, while also acknowledging the patient’s desire for fast relief.

DEFINITION AND DIAGNOSIS OF CONSTIPATION

Definition

Chronic constipation is typically defined as unsatisfactory defaecation that includes infrequent stools, difficulty passing stools, or both, for at least three to six months. ‘Difficult stool passage’ can mean straining, feeling like it is hard to pass stool, not feeling completely empty after a bowel movement, having hard or lumpy stools, taking a long time on the toilet, or needing to use manual manoeuvres like digital evacuation.

Diagnosis

An accurate diagnosis is the first step toward effective management. This involves a detailed patient history, a physical examination and using standardised diagnostic criteria.

Using standardised diagnostic criteria

The Rome IV criteria are a widely used set of symptom-based guidelines for diagnosing functional constipation, which is a diagnosis made after ruling out physical or organic causes. To meet the criteria, a patient must experience two or more of the following for the last three months, with symptoms starting at least six months ago:

- Straining during more than ¼ (25%) of defaecations

- Lumpy or hard stools (Bristol Stool Form Scale 1-2) more than ¼ (25%) of defaecations

- Sensation of incomplete evacuation more than¼ (25%) of defaecation

- Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage more than ¼ (25%) of defaecation

- Fewer than three spontaneous bowel movements per week

- Manual manoeuvres to facilitate more than¼ (25%) of defaecations (e.g., digital evacuation, support of the pelvic floor)

- Loose stools are rarely present without the use of laxatives

- Insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome

History taking

The initial assessment must begin with a thorough history, covering the patient’s lifelong stool frequency, consistency and any need for straining or manual assistance.

Many people feel constipated even with daily bowel movements, which underscores the need to understand the quality of defaecation, not just the frequency. The Bristol Stool Form Scale is an excellent tool for both patients and doctors to objectively describe stool consistency.

It is also critical to ask about “red flag” symptoms such as rectal bleeding, abdominal pain or swelling, which could indicate a more serious condition like colorectal cancer.

Physical Exam

Following the history, a physical examination should include palpating the abdomen for tenderness or masses and performing a careful digital rectal examination. The rectal exam is crucial for identifying anal issues like strictures or fissures, neurological problems and assessing pelvic floor function. It is a very sensitive tool for GPs to screen for pelvic floor dysfunction by checking anal tone and how the muscles contract during a simulated bowel movement, which can help streamline diagnosis and guide referrals.

UNDERSTANDING THE TYPES OF CHRONIC CONSTIPATION

Chronic constipation is not a single condition but a syndrome with different underlying causes. The three main types are slow transit constipation (STC), obstructed defaecation syndrome (ODS), and normal transit constipation (NTC). Identifying the correct type is key to choosing the right treatment.

SLOW TRANSIT CONSTIPATION

Definition

Slow transit constipation (STC) is defined by reduced motility in the colon, which means waste moves through the large intestine too slowly. It is the least common type, affecting about 2-4% of the population, but it often leads to severe, hard-to-treat symptoms.

Symptoms

Patients with STC typically have infrequent bowel movements, a reduced urge to defaecate, and may also suffer from abdominal pain and nausea. It is most common in young women between the ages of 20 and 40. A classic case is a young woman who has a bowel movement only once every one to two weeks, with no urge in between, and has unsuccessfully tried many different laxatives.

Cause

STC is considered a neuromuscular disorder of the colon. The problem lies with the enteric nervous system, which controls the colon’s muscle contractions. Diagnostic tests often show reduced contractions and a delayed transit time. Histological studies of colon tissue from STC patients often reveal a reduced number of interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs), which act as the colon’s pacemakers. The exact cause is unknown, but theories include autoimmune issues and hormonal influences, given the strong female predominance. Understanding that STC is a genuine neuromuscular disorder, not just a ‘functional’ issue, is crucial because it implies that patients may need more advanced testing and more aggressive treatments.

A key diagnostic test is the transit marker study, where a patient swallows a capsule with radio opaque markers and an X-ray is taken five days later. If five or more markers remain scattered throughout the colon, it suggests STC.

OBSTRUCTED DEFAECATION SYNDROME

Definition

Obstructed defaecation syndrome (ODS) is a type of constipation where the main problem is difficulty emptying the rectum.

Symptoms

Key symptoms include feeling a blockage, not being able to empty completely, excessive straining, and needing to use manual manoeuvres like pressing on the perineum or vagina to help pass stool. The mention of these manoeuvres is a strong clinical clue for GPs that points towards ODS.

Cause

ODS can be caused by two main types of problems:

Pelvic floor dyssynergia (physiological): This is a coordination failure. During a normal bowel movement, the rectal pressure increases while the anal sphincter and pelvic floor muscles relax. In dyssynergia, these muscles may contract instead of relaxing (paradoxical contraction) or fail to relax enough.

Posterior compartment prolapse (anatomical): This involves structural problems where pelvic organs shift downwards. Examples include a rectocele (a bulge of the rectal wall into the vagina where stool can get trapped), an enterocele (protrusion of the small intestine into the space between the rectum and vagina), and rectal prolapse (where the rectum telescopes into itself or protrudes out of the anus).

These anatomical issues are often caused by weakened pelvic floor muscles due to factors like pregnancy, childbirth and menopause, or from chronic straining. This creates a vicious cycle where constipation and straining worsen the prolapse, which in turn makes the obstructed defaecation worse.

Diagnosis

A careful digital rectal examination is essential to differentiate between these physiological and anatomical causes. Specialised tests like defecography (an X-ray or MRI that visualises the defaecation process) and anorectal manometry (which measures anal pressures) are used for a definitive diagnosis.

NORMAL TRANSIT OR IDIOPATHIC CONSTIPATION

Definition

Normal transit constipation (NTC), also called chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) when the cause is unknown, is the most common type.

Symptoms

Patients with NTC have typical constipation symptoms like straining and hard stools but tests show that their colonic transit time is normal. The stool may be harder than usual, making it difficult to pass even though it moves through the colon at a normal speed.

NTC often overlaps with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C), but the key difference is that IBS-C is defined by abdominal pain that gets better after a bowel movement, which is not a primary feature of NTC.

Cause and Diagnosis

The cause of NTC is often multifactorial and not well understood. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, made after ruling out other causes. As the cause is often “idiopathic”(unknown), the main treatment approach for GPs is to focus on modifiable lifestyle and dietary factors like increasing fluid, fibre and exercise.

Management of Constipation in the Primary Healthcare Setting

Effective management starts with patient education and lifestyle changes, followed by a stepwise introduction of medications if needed.

Dietary and Lifestyle Advice

Fluid Intake: While drinking more water alonemay not help unless the patient is dehydrated, it is essential when increasing fibre intake. Patients should be advised to drink 8-10 cups (2-2.5 liters) of water and non-caffeinated drinks daily.

Dietary Fibre: Fibre adds bulk to the stool and helps it move through the colon. Both soluble (oats, apples, bananas) and insoluble (leafy greens, nuts, seeds) fibres are beneficial. Prunes and dragonfruit are especially effective. It is important to avoid high-fat foods and excessive cheese.

However, moderation in fibre intake is key, as too much can cause bloating and cramping, and can even worsen constipation by creating too much bulk, especially in patients with slow transit.

Physical Activity: Regular exercise helpsimprove bowel motility. Patients should be encouraged to be active on most days of the week.

Bowel Habits: Patients should be advised not to ignore the urge to have a bowel movement. Using a small stool to elevate the feet while on the toilet can also help by straightening the anorectal angle. It is also important to correct the misconception that a daily bowel movement is necessary for health; having a bowel movement anywhere from three times a day to three times a week can be normal.

Pharmacological Interventions

If lifestyle changes are not enough, medications can be used.

First-Line Therapies (Over-thecounter): These include bulk-forming agents like psyllium (Metamucil) andosmotic laxatives like polyethyleneglycol (Forlax) or lactulose. Bulk-forming agents absorb water to increase stool volume, but require adequate fluid intake to work properly. Osmotic laxatives draw water into the intestines to soften the stool.

Second-Line Therapies: Stimulant laxatives like bisacodyl (Dulcolax) or senna (Senokot) cause the intestinal walls to contract. They are effective for short-term use. Concerns about long-term use causing damage to the colon have not been proven in studies. Enemas and suppositories are used for more immediate relief or for faecal impaction.

Prescription Medications: For difficult cases, newer agents may be prescribed. These include intestinal secretagogues (e.g., lubiprostone, linaclotide) which increase fluid secretion in the gut, and serotonin agonists (e.g., prucalopride) which stimulate motility. These medications are significantly more expensive than standard laxatives and should be reserved for cases where first-line treatments have failed.

Clinical effectiveness must be balanced with cost and patient expectations, hence it is important to startwith cost-effective, proven first-line laxatives and with the rationale clearly explained to patients.

WHEN CONSTIPATION SHOULD BE REFERRED FOR SPECIALIST CARE

While most constipation can be managed in primary care, certain “red flag” symptoms require urgent referral to a specialist like a gastroenterologist or colorectal surgeon. These red flags include:

- New or worsening severe constipation

- A sudden change in bowel habits

- Inability to pass stool or gas

- Unexplained weight loss

- Rectal bleeding or blood in the stool

- Anaemia

- Persistent abdominal pain or vomiting

- A family history of colon cancer

These symptoms suggest a serious underlying condition like cancer or a bowel obstruction and require immediate investigation, often with a colonoscopy.

If there are no red flags, a referral is still warranted if the patient’s symptoms persist despite making optimal lifestyle changes and first-line medications. These patients may need specialised testing to diagnose STC or ODS, which might require more advanced treatments, bio feedback therapy or even surgery.

CONCLUSION

Constipation is a common problem that significantly affects quality of life, and GPs in Singapore are on the front lines of managing it. A clear diagnosis, using tools like the Rome IV criteria and a thorough physical exam including a digital rectal assessment, is crucial for distinguishing between the different types of constipation. GPs must understand that a patient’s perception of constipation is subjective and that they can proactively screen for pelvic floor issues.

While lifestyle changes and first-line medications are the mainstays of treatment, it is critical to be vigilant for “red flag” symptoms that require immediate specialist referral. For the most complex cases, multidisciplinary centres like the SingHealth Duke-NUS Pelvic Floor Disorders Centre offer the best path to effective treatment. By taking a systematic, patient focused approach and knowing when to refer, GPs can dramatically improve the outcomes and wellbeing of patients suffering from chronic constipation.

Clin Asst Prof Cherylin Fu

Dr Cherylin Fu is a senior consultant surgeon under the Department of Colorectal Surgery at Singapore General Hospital and Department of Surgical Oncology at the National Cancer Centre Singapore. She is also the Director of the Gastrointestinal Functional Unit and Pelvic Floor Disorders Service at Singapore General Hospital.

Dr Fu manages colorectal cancer, benign colorectal diseases and proctology and pelvic floor disorders such as rectal prolapse and faecal incontinence. She also has a keen interest in advanced laparoscopic techniques such as Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision for rectal cancer and Natural Orifice Specimen Extraction.

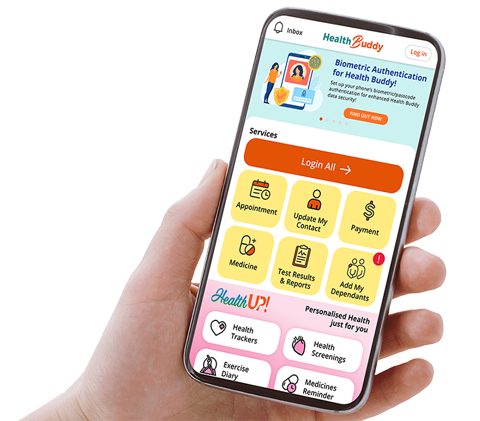

GPs can call the SingHealth Duke-NUS Pelvic Floor Disorders Centre for appointments at the following hotlines:

Singapore General Hospital 6326 6060

Changi General Hospital 6788 3003

Sengkang General Hospital 6930 6000

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital 6692 2984