get insufficient sleep on school nights and attempt to catch up on sleep on weekend nights.

Sleep is important for optimal cognitive performance and health. However, many adolescents do not get adequate sleep. This short review examines factors that contribute to insufficient sleep during adolescence and potential consequences of poor sleep on well-being and metabolic health. Possible solutions for improving sleep and health outcomes in adolescents are also discussed.

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE SLEEP

Sleep duration tends to decrease during adolescence compared with earlier in childhood. With increasing age, adolescents usually go to bed later due to the convergence of biological and socio-cultural factors (discussed below)

1, which can result in reduced time in bed for sleep on school nights.

Sleep duration tends to decrease during adolescence compared with earlier in childhood. With increasing age, adolescents usually go to bed later due to the convergence of biological and socio-cultural factors (discussed below)

1, which can result in reduced time in bed for sleep on school nights.

Consequently, many adolescents are exposed to partial sleep deprivation during the school week and exhibit ‘catch-up’ sleep on weekends (Refer to Figure 1).

The National Sleep Foundation (NSF) in the United States recommends that adolescents get 8 to 10 hours of sleep per night for optimal health and cognitive functioning 2.

Based on data collected in Singapore, about 80% of adolescents report getting less sleep than what is recommended by the NSF. This is alarming because insufficient sleep in adolescents has been linked with impaired learning and mood disturbances 3.

Adolescence is associated with biological changes that affect the circadian timing of sleep. There is a phase delay shift in circadian rhythms during adolescence that results in a preference for later bedtimes and wake-up times. Hence, adolescents at a more mature Tanner stage have later bedtimes and a delayed circadian rhythm of the sleep-promoting hormone melatonin 4.

The ability to fall asleep also depends on how long a person has been awake, due to the build-up of homeostatic sleep pressure. There is evidence that the build-up of sleep pressure during wakefulness occurs more slowly in adolescents compared with younger children 5, which makes it easier for post-pubertal children to delay their bedtime.

Therefore, contrary to popular belief, achieving earlier bedtimes on school nights is not simply a matter of exercising better self-discipline. Rather, adolescents are biologically predisposed to go to bed later than younger children and adults.

Socio-cultural factors also contribute to changes in sleep patterns. With increased autonomy and independence, adolescents are more likely to make their own decisions regarding when to go to bed. For example, many adolescents may be willing to exchange sleep for more study time, despite evidence that shorter sleep durations are associated with poorer academic performance 6.

The use of electronic devices at night is also more common during adolescence compared with earlier childhood, and the ability to socialise with friends is facilitated by the proliferation of smartphones and tablets in this age group. The use of electronic devices near bedtime has been shown to contribute to later and shorter nocturnal sleep 7, and exposure to light emitted by these devices may contribute to delayed circadian rhythms and increased sleepiness on the following morning 8.

EFFECTS OF INSUFFICIENT SLEEP

The most obvious sign of insufficient sleep is daytime sleepiness. Based on data collected in Singapore, most adolescents extend their sleep duration by more than 2 hours on weekends, suggesting that they are not getting sufficient sleep on school nights (Dr. Joshua J. Gooley, Duke-NUS, unpublished).

Adolescents with shorter sleep are also more likely to engage in coping mechanisms for their tiredness, including taking naps and using caffeine with the explicit purpose of staying awake during the daytime. We have also found that most adolescents in Singapore rely on a parent or alarm to wake them up in the morning, indicating that their nocturnal sleep is truncated by having to get ready for school.

Insufficient sleep impairs cognitive processes that are essential for optimal learning and academic success. Studies conducted by Duke-NUS researchers have demonstrated that adolescents who are exposed to a week of sleep restriction (i.e., short sleep each night) exhibit cumulative negative effects on attention, processing speed, and working memory 9.

The ability to learn and recall facts is also impaired by sleep restriction 10, which raises important concerns about whether the ability of students to learn is compromised by recurrent exposure to partial sleep deprivation.

In fact, recent work in Singapore indicates that the catch-up sleep that adolescents get on weekends may not be sufficient for their attention to recover fully 11.

Sleep restriction also has cumulative negative effects on mood 9, and adolescents with short sleep on school nights are more likely to report depressive symptoms.

Research findings in Singapore are consistent with those in the United States, in which adolescents with later bedtimes and shorter sleep durations were more likely to suffer from depressive symptoms and suicide ideation 12. These studies suggest that sleep is important for adolescents’ mental health.

Over that past decade, several studies have shown that exposure to short sleep in childhood is associated with obesity 13. Using self-reported data collected in Singapore, we have found that the odds of being overweight are about 2-fold higher in adolescents exposed to short sleep (< 7 hours on school nights) compared with those with healthy sleep (8 - 10 hours). Other researchers have shown that short sleep may contribute to overeating and increased sedentary activity 14,15.

Hence, the epidemic of short sleep among adolescents should be a cause of concern for Singapore’s War on Diabetes.

Notably, exposure to short-term sleep restriction has been associated with decreased insulin sensitivity in healthy adolescents 16, and extending sleep duration has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in healthy adults regularly exposed to sleep restriction 17,18. Future studies in adolescents should therefore examine whether sleep protects against the development of impaired glucose metabolism.

POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS FOR IMPROVING SLEEP AND HEALTH OUTCOMES

Because sleep is important for cognitive performance and health, it is important to consider strategies for improving sleep behaviour in adolescents.

As highlighted above, it can be difficult for adolescents to advance their sleep schedule due to age-dependent changes in circadian timing and sleep homeostasis. Nonetheless, the tendency for adolescents to go to bed late can be minimised by improving their sleep hygiene practices.

This includes educating adolescents and their parents about the importance of sleep for well-being so that they can both make informed decisions that lead to behaviours conducive to better sleep habits.

For example, adolescents whose bedtime is set by their parents have earlier bedtimes, more sleep, and less daytime fatigue 19, suggesting that parental involvement can facilitate improvements in sleep behaviour and cognitive functioning.

It is also important that teachers, policy makers, and healthcare providers are adequately informed on the benefits of healthy sleep so that they can encourage and reinforce healthy sleep habits.

An alternative approach for extending nocturnal sleep duration is to make changes that would allow for later wakeup times. The American Academy of Paediatrics (AAP) issued a policy statement urging middle/high schools to start no earlier than 8:30am, with the aim of allowing more students to achieve a healthy amount of sleep each night 20.

Consistent with this recommendation, a large body of evidence collected in the United States has shown that delaying school start time increases sleep duration on school nights, with many studies also demonstrating improved mood, less falling asleep in class, and better grades 6,21.

In Singapore, almost all local schools start about an hour earlier than what the AAP considers a healthy school start time in adolescents.

Recently, Nanyang Girls’ High School delayed their school start time by 45 minutes from 7:30 am to 8:15 am 22.After the change in school start time, adolescents reported more time in bed for sleep and fewer depressive symptoms, assessed up to several months after the intervention (Dr. Michael Chee, Duke-NUS, unpublished).

These results suggest that adopting later school start times may have sustained benefits for adolescents’ sleep and well-being.

CONCLUSION

In summary, it can be challenging for adolescents to get sufficient sleep on school nights. Paediatricians and thought leaders in sleep research can have a positive impact on sleep behaviour in adolescents by educating the public about the importance of sleep for adolescents’ cognition and health.

It is important to empower parents and their children to make informed, healthy decisions about the timing and duration of their nocturnal sleep. Late-night activities that are stimulating and that delay bedtimes should be avoided because they contribute to short nocturnal sleep and can negatively affect learning and mood during the daytime.

Finally, schools should be encouraged to integrate instructional materials on sleep into multiple areas of the curriculum, and to consider whether administrative changes can be made (e.g., changing school start times, improving transportation options, or reducing evening workload) to foster better sleep, learning, and health outcomes in adolescents.

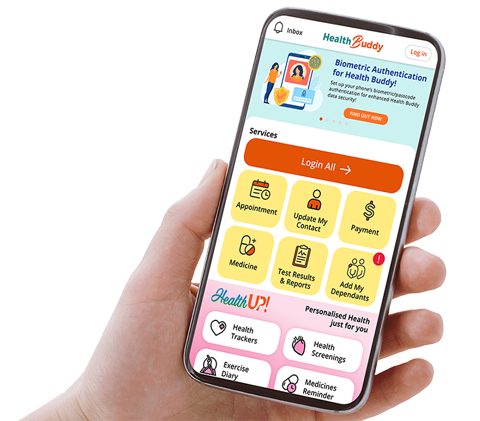

For appointments at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Sleep Centre, GPs can call through the GP Appointment Hotline at 6321 4402 for more information.

By: Associate Professor Joshua J. Gooley, Neuroscience and Behavioural Disorders Programme, Duke-NUS Medical School; SingHealth Duke-NUS Sleep Centre

Dr. Joshua J. Gooley is an Associate Professor in the Centre for Cognitive Neuroscience, and the Neuroscience and Behavioural Disorders Programme at Duke-NUS Medical School.

He is Principal Investigator of the Chronobiology and Sleep Laboratory, located in the SingHealth Investigational Medicine Unit at Singapore General Hospital. Dr. Gooley’s research programme at Duke-NUS focuses on understanding effects of sleep and circadian rhythms on cognition and health.

References

1. Carskadon, M. A. Sleep in adolescents: the perfect storm. Pediatr Clin North Am 58, 637-647, doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.003 (2011).

2 Hirshkowitz, M. et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health 1, 40-43 (2015).

3 Carskadon, M. A. Sleep’s effects on cognition and learning in adolescence. Prog Brain Res 190, 137-143, doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53817- 8.00008-6 (2011).

4 Carskadon, M. A., Vieira, C. & Acebo, C. Association between puberty and delayed phase preference. Sleep 16, 258-262 (1993).

5 Jenni, O. G., Achermann, P. & Carskadon, M. A. Homeostatic sleep regulation in adolescents. Sleep 28, 1446-1454 (2005).

6 Chaput, J. P. et al. Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 41, S266-282, doi:10.1139/apnm-2015-0627 (2016).

7 Cain, N. & Gradisar, M. Electronic media use and sleep in school-aged children and adolescents: A review. Sleep Med 11, 735-742, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2010.02.006 (2010).

8 Chang, A. M., Aeschbach, D., Duffy, J. F. & Czeisler, C. A. Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 1232-1237, doi:10.1073/pnas.1418490112 (2015).

9 Lo, J. C., Ong, J. L., Leong, R. L., Gooley, J. J. & Chee, M. W. Cognitive Performance, Sleepiness, and Mood in Partially Sleep Deprived Adolescents: The Need for Sleep Study. Sleep 39, 687-698, doi:10.5665/sleep.5552 (2016).

10 Huang, S. et al. Sleep Restriction Impairs Vocabulary Learning when Adolescents Cram for Exams: The Need for Sleep Study. Sleep 39, 1681-1690, doi:10.5665/sleep.6092 (2016).

11 Lo, J. C. et al. Neurobehavioral Impact of Successive Cycles of Sleep Restriction With and Without Naps in Adolescents. Sleep 40, doi:10.1093/sleep/zsw042 (2017).

12 Gangwisch, J. E. et al. Earlier parental set bedtimes as a protective factor against depression and suicidal ideation. Sleep 33, 97-106 (2010).

13 Cappuccio, F. P. et al. Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep 31, 619-626 (2008).

14 Spaeth, A. M., Dinges, D. F. & Goel, N. Effects of Experimental Sleep Restriction on Weight Gain, Caloric Intake, and Meal Timing in Healthy Adults. Sleep 36, 981-990, doi:10.5665/sleep.2792 (2013).

15 Stea, T. H., Knutsen, T. & Torstveit, M. K. Association between short time in bed, health-risk behaviors and poor academic achievement among Norwegian adolescents. Sleep Med 15, 666-671, doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2014.01.019 (2014).

16 Klingenberg, L. et al. Acute Sleep Restriction Reduces Insulin Sensitivity in Adolescent Boys. Sleep 36, 1085-1090, doi:10.5665/sleep.2816 (2013).

17 Killick, R. et al. Metabolic and hormonal effects of ‘catch-up’ sleep in men with chronic, repetitive, lifestyle-driven sleep restriction. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 83, 498-507, doi:10.1111/cen.12747 (2015).

18 Leproult, R., Deliens, G., Gilson, M. & Peigneux, P. Beneficial impact of sleep extension on fasting insulin sensitivity in adults with habitual sleep restriction. Sleep 38, 707-715, doi:10.5665/sleep.4660 (2015).

19 Short, M. A. et al. Time for bed: parent-set bedtimes associated with improved sleep and daytime functioning in adolescents. Sleep 34, 797-800, doi:10.5665/SLEEP.1052 (2011).

20 Adolescent Sleep Working Group; Committee on Adolescence; Council on School Health. School start times for adolescents. Pediatrics 134, 642-649, doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1697 (2014).

21 Wheaton, A. G., Chapman, D. P. & Croft, J. B. School Start Times, Sleep, Behavioral, Health, and Academic Outcomes: A Review of the Literature. J Sch Health 86, 363-381, doi:10.1111/josh.12388 (2016).

22 Koh, D. A big difference in students, after Nanyang Girls starts school later at 8:15am, (2017).