INSOMNIA is a common sleep disorder in Singapore, with a local reported rate of 15.3% 1. A recent local study also found that 13.7% of older adults aged 60 and above, were reported to experience insomnia 2.

The diagnostic criteria of chronic insomnia, from the ICSD-3 (International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd Edition) and the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition) share many similarities, due to the close collaborations between the work groups.

Some of the salient features, are a difficulty in initiating sleep, in maintaining sleep or an early morning awakening, resulting in socio-occupational impairments. These episodes of insomnia should occur at least 3 times per week, for at least 3 months.

In the past, there used to be various subtypes of insomnia, and there were also attempts to differentiate between the primary and secondary causes of insomnia. However, the patients tend to have multiple contributing causes, as well as symptoms that span across various subtypes. Therefore, the current diagnostic criteria is simple, yet more practical 3.

It can be challenging to manage insomnia in primary care. This is partly due to the lengthy consultation that is required to ascertain the contributing factors, and the advice is lengthy as well. In Singapore, there are also stringent regulations of hypnotic agents, such as benzodiazepines.

HOW GPs CAN ASSESS

It is important to ask for more details of the sleep patterns and the daily routine (Refer to Table 1), so as to elicit the contributing factors of the insomnia.

The next step, will be to screen for the psychiatric conditions, such as depression and anxiety disorders, as well as other sleep disorders, such as the Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) and Obstructive Sleep Apnoea (OSA).

It will be helpful to find out what methods have been tried, as well as to ask for the expectations of the patient. If possible, a corroborative history from the partner, and the family members of the patient, should be obtained.

Patients often report experiencing anxiety, associated with automatic negative thoughts, as the night falls. Some of these could be “I will not be able to perform well at work tomorrow”, “I will drive poorly” and “my friends will notice that I look tired.” These thoughts and feelings, make the reaching of the state of relaxation that is required for sleep, harder.

A mental state examination, a physical examination and appropriate investigations as guided by the history, should follow. Sleep logs or sleep diaries can give a clearer account, and may also be helpful for the monitoring of progress.

In a Sleep Centre, investigations such as polysomnography (a type of sleep study), and multiple sleep latency tests, are ordered. This is to exclude the diagnosis of other sleep disorders (such as OSA, a periodic limb movement disorder and narcolepsy), and are not used to diagnose insomnia.

Table 1 Important Sleep History to Elicit | |

|---|---|

| 1. ONSET AND DURATION: | |

| • Days, weeks or months | |

| 2. TIMES: | |

| • The times at which the patient goes to bed, falls asleep and wakes up, as well as any intermittent awakenings that occur | |

| 3. SLEEP HYGIENE: | |

| • Naps (duration and time) • Drinks with stimulants (coffee, tea and cola) • Exercise | • Use of the bed for other activities • Irregular sleep-wake timing |

| 4. ANY RECENT STRESSOR | |

| 5. ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS: | |

| • Noise • Shift work | • Uncomfortable surroundings |

| 6. TO SCREEN FOR PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS: | |

| •

Depression Low mood, appetite changes, withdrawal from pleasurable activities, a lack of meaning in life • Anxiety Disorders Excessive worries over the circumstances of life, and not only worries about poor sleep | •

Alcohol or Substance Use Disorders A history of frequent alcohol use or illicit drug use |

| 7. TO SCREEN FOR OTHER SLEEP DISORDERS: | |

| •

Obstructive Sleep Apnoea (OSA) The partner of the patient observed signs of snoring and a gasping for air • Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS) Restlessness, discomfort in the limbs precipitated by rest | •

Periodic Limb Movement Disorder Jerks observed by the partner of the patient • Circadian Rhythm Disorders Sleep and waking up at unusual times |

| 8. TO SCREEN FOR MEDICAL-RELATED ISSUES: | |

| • Other medical problems (for e.g., urinary frequency and chronic pain) | • Medications (for e.g., theophylline and beta-blockers) |

| 9. CONSEQUENCES DURING THE DAY: | |

| • How it impacts relationships, leisure, school and work activities | |

BEHAVIOURAL MANAGEMENT

Cognitive-behavioural therapy, in the management of insomnia, is a first-line treatment, and it might be better than pharmacological treatment in the long-term 4. It consists of various techniques, that may target either the behavioural or cognitive aspects of insomnia.

Behavioural techniques include advice on sleep hygiene, relaxation techniques and stimulus control. Cognitive techniques focus on challenging the negative and distorted thoughts, and replacing it with helpful ones. All these techniques take time to learn, more effort to execute and may not offer same-day results.

However, they do not have the risk of a dependence, or the other side effects, of medications. Some patients may have already tried some of these methods with limited success. It takes patience to explain that the causes are multifactorial. Hence, the interventions should also have a multi-pronged approach, and should be persisted.

Educating patients on good sleep hygiene is straightforward and essential. This includes having a regular sleep-wake time even during the weekends, avoiding long naps and avoiding coffee, tea and drinks with stimulants. The information is easily accessible on the Internet, and can be printed out for the patients.

Stimulus control is a type of conditioning, where the patient pairs the concept of sleepiness with the bed. They are told to go to the bed, only when feeling sleepy. If they are unable to sleep after 15 minutes, they are told to get out of bed, and to return again only when they feel sleepy.

Relaxation techniques, such as progressive muscle relaxation, deep breathing exercises, and mindfulness techniques, can help the patient achieve a state of relaxation. The instructional videos are easily found on the Internet.

The patients who face stressors may benefit from counselling. The primary care doctor can also consider referring the patient to external agencies, such as to a nearby Family Service Centre. The website of the Agency for Integrated Care carries a list of other counselling centres, that the doctors can refer to.

PHARMACOLOGICAL AGENTS

All medications that are sedative may increase the risk of falls, especially in elderly patients, or in those with multiple medical problems. This can result in hip fractures and resulting consequences. It is important to discuss the pros and cons, and to make a joint decision with the patient. Medications should be started judiciously at low doses, and be carefully monitored.

Antihistamines are sedative, and it is commonly used by doctors for insomnia. It is safe, the least likely to cause a dependence, and inexpensive. The ones that are commonly prescribed, are hydroxyzine and chlorpheniramine. However, patients often report a drowsiness on the next day. As it antagonises the muscarinic cholinergic receptors, it may result in a urinary retention and an impaired cognitive function.

Benzodiazepines are effective 5 and inexpensive. It works by potentiating GABA actions, via specific benzodiazepine receptors on the GABA-chloride ion channels. However, it should not be the first-line choice, as it carries a risk of developing a dependence (which is now termed as a Substance Use Disorder in the DSM-5).

The tolerance will result in escalating doses to achieve the same sedating effects, and the patient may experience withdrawal syndromes, including life-threatening ones, for those who used high doses. This is similar to the onset of delirium tremens during alcohol withdrawal.

Therefore, benzodiazepines are best prescribed in small quantities, and patients should be told to use it intermittently. It should be stopped within 4 weeks.

It is best avoided in those patients with personality disorders, or those with a history of taking illicit medications.

It should be used cautiously in those with a respiratory failure, or a liver impairment.

The other side effects of benzodiazepines include falls, amnesia, an impaired cognitive and motor performance, daytime sleepiness and paradoxical reactions.

For elderly patients, benzodiazepines with shorter half-lives (such as lorazepam or alprazolam) should be chosen to reduce the risk of falls. For adults, the ones with longer halflives (for e.g., diazepam) have a lower risk of dependence, and is helpful for those with intermittent awakenings and early morning awakenings.

Benzodiazepine receptor agonists also consist of non-benzodiazepines, such as zolpidem and zopiclone. However, it also carries the risk of a dependence. Hence, it should be used as cautiously as benzodiazepines. It is not helpful in reducing anxiety, and does not abort seizures. It has also been linked to sleepwalking and sleep-related eating 6.

Antidepressants are used for insomnia, because it does not carry the risk of a dependence. However, the use is mostly off-label for insomnia, with the exception of doxepin. It is helpful, if the patient also has depression or anxiety disorders.

Some antidepressants include trazodone, mirtazapine and tricyclic antidepressants. The 2nd generation antipsychotics, that are sedative, increase the risk of a metabolic syndrome. Therefore, they are often less frequently considered.

Recently, prolonged-release melatonin has become available in Singapore. It may be prescribed to patients above the age of 55, for up to 3 months, and has been useful for insomnia 7. A possible mechanism, could be a decrease in the production of melatonin in the older patients. Agomelatine, a new antidepressant that also acts on melatonin receptors, may be helpful for insomnia in the patients with depression.

WHEN TO REFER TO A SLEEP SPECIALIST

Insomnia should be treated at the primary care level. However, when other sleep disorders such as OSA or RLS are detected, or when the patient has failed to respond to the medications, they may be referred to a Sleep Disorders Unit.

CONCLUSION

Insomnia is a common disorder in Singapore. It is important to elicit a detailed history, so as to identify the plethora of contributing factors. Co-morbidities, such as depression, anxiety disorders, and other sleep disorders, should be screened.

Behavioural techniques may be tedious, but carry long-term benefits and lower risks. Sedating agents can cause falls, and benzodiazepine receptor agonists, although effective, may increase the risk of a dependence. Therefore, it should be cautiously used for only short periods.

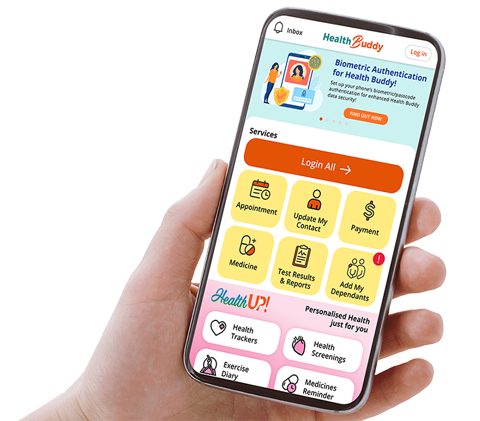

GPs can call for appointments through the GP Appointment Hotline at 6472 2000 for more information.

By: Adjunct Assistant Professor Victor Kwok, Head and Consultant, Department of Psychiatry, Sengkang General Hospital; Duke-NUS Medical School; SingHealth Duke-NUS Sleep Centre

Dr. Victor Kwok is a Consultant Psychiatrist and the Head of Psychiatry at Sengkang Health. He has a special interest in General Psychiatry, Liaison Psychiatry and Eating Disorders. He has been appointed as the Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Duke- NUS Medical School. He will be involved in the Sleep Disorders Unit at the Sengkang General Hospital.

References

1. Yeo BK, Perera IS, Kok LP, Tsoi WF. Insomnia in the community. Singapore Med J. 1996 Jun;37(3):282-4.

2. Sagayadevan V, Abdin E, Binte Shafie S, Jeyagurunathan A, Sambasivam R, Zhang Y, Picco L, Vaingankar J, Chong SA, Subramaniam M. Prevalence and correlates of sleep problems among elderly Singaporeans. Psychogeriatrics. 2017 Jan;17(1):43-51.

3. Edinger JD, Wyatt JK, Stepanski E, et al. Testing the reliability and validity of DSM-IV-TR and ICSD-2 insomnia diagnosis: results of a multi- method/multi-trait analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(10):992–1002.

4. Mitchell MD, Gehrman P, Perlis M, Umscheid CA. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13(1):40.

5. Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia. CMAJ. 2000;162(2):225–233.

6. Hoque R, Chesson AL., Jr. Zolpidem-induced sleepwalking, sleep-related eating disorder, and sleep-driving: fluorine-18-flourodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography analysis, and a literature review of other unexpected clinical effects of zolpidem. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:471–6.

7. Wade AG, Ford I, Crawford G, et al. Nightly treatment of primary insomnia with prolonged release melatonin for 6 months: a randomised placebo controlled trial on age and endogenous melatonin as predictors of efficacy and safety. BMC Med. 2010;16:51.