Diagnosis of young-onset dementia is often delayed due to the atypical and heterogeneous nature of its presentation. A systematic clinical approach to assessment at primary care can identify such patients early for better outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, the number of persons with dementia is expected to increase from 40.1 million in 2015 to 55.4 million in 2025.1 In approximately 5% of persons with dementia, symptom onset occurs below the age of 65. This is defined as young-onset dementia (YOD).

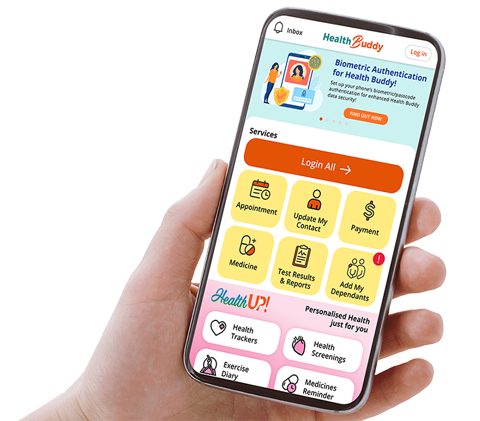

More than 100 cases of YOD or young-onset mild cognitive impairment are diagnosed each year at the National Neuroscience Institute (NNI). Compared with late-onset dementia (LOD), persons with YOD incur greater economic and societal burden.2

Early diagnosis and treatment is therefore crucial, as it results in less cognitive decline, better clinical and functional status, as well as lower mortality.

UNDERSTANDING THE DIAGNOSTIC DELAY

However, the diagnosis of YOD is often delayed. As an illustration, in our local cohort of persons with biomarker-proven early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the mean duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis was 2.6 years.

Key differences between YOD and LOD in terms of aetiologies, clinical presentation and disease course may explain this observation.

In LOD, 61% of cases are due to AD and most patients present with classical symptoms of dementia such as short-term memory loss.

Conversely in YOD, our local data shows that only 35% of cases are due to AD – and amongst these, more than one third may have atypical or non-amnestic presentations (Table 1).

The remaining 65% of cases are due to vascular dementia, frontotemporal dementia, Parkinson disease dementia and others (e.g., autoimmune, metabolic and infective causes) (Figure 1).

There is considerable clinical overlap between these aetiologies, yet there are distinguishing features that guide diagnosis.

In this article, we will discuss two case studies that highlight the protean clinical presentations of YOD, and provide a clinical approach that may facilitate early recognition and specialist referral by the general practitioner (GP).

Case Studies

CASE A: DELAYED DIAGNOSIS DUE TO NON-SPECIFIC VISUAL SYMPTOMS

Background

A 62-year-old engineer presents with a two-year history of progressively visual symptoms. He first noticed difficulty with making PowerPoint presentations, and subsequently complained of increasing difficulties with vision that were non-specific in nature.

Diagnosis

Multiple visits to the ophthalmologist and optometrist did not show any ocular pathology. He later developed short-term memory loss that affected his daily function and work, which triggered a consult to a neurologist.

Assessment

On examination, the main neurological finding was that of simultagnosia, whereby his ability to perceive multiple elements of an object or scene simultaneously was severely impaired. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score was 22/30, with deficits in visuospatial and executive function.

Brain scans

An MRI scan of the brain showed left hippocampal and bilateral parieto-occipital lobe atrophy suggestive of AD. To improve diagnostic certainty, an amyloid positron emission tomography (amyloid PET) scan was done. It showed amyloid deposition in the cerebral cortex, thus confirming the diagnosis of dementia secondary to early-onset AD.

| This case is typical of the posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) or 'visual' variant of AD. The insidious and non-specific nature of visual symptoms often leads to a futile – and often protracted – hunt for an ophthalmologic cause, causing significant diagnostic delay. A neurodegenerative disease like AD may only be suspected later in the disease course when additional symptoms such as amnesia, executive dysfunction or language difficulties develop. Indeed, in NNI’s PCA cohort, patients presented at a mean of 3.9 years after their onset of symptoms. |

CASE B: DELAYED DIAGNOSIS AS BEHAVIOURAL SYMPTOMS SUGGESTED A PSYCHIATRIC DISORDER

Background

A 58-year-old man presented with cognitive and behavioural symptoms for three years. He had difficulties with executive function such as managing his finances, driving and keeping track of goods deliveries.

He became progressively apathetic, with reduced participation in family conversations and a lack of interest in his hobbies, and spent his free time staring at the TV without turning it on.

He was also disinhibited, having urinated on the ground while his family was praying at the Qingming festival, and again while in a public elevator. He demonstrated no insight into the inappropriateness of his actions.

He developed ritualistic habits such as going to work at exactly 7.20 am, as well as rigid dietary preferences, consuming the same food and drink for every meal for months on end.

Diagnosis

In the neurology clinic, he demonstrated poor awareness of his condition and smiled emotionlessly throughout the consultation.

Assessment

Neurological examination was unremarkable for any neurological deficits. On assessment of speech and language, he demonstrated echolalia, a speech disorder where he meaninglessly repeated words spoken to him. MMSE score was 19/30.

He underwent an MRI scan of the brain, which showed bilateral frontal lobe atrophy. Routine blood investigations were normal. Based on his clinical presentation and neuroimaging, a diagnosis of behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) was made.

While the prominent behavioural symptoms may suggest a psychiatric disorder, his constellation of symptoms (executive dysfunction, apathy, disinhibition, ritualistic/compulsive behaviour, dietary changes) are typical of bvFTD. In addition, the presence of prominent executive dysfunction would also suggest dementia rather than psychiatric illness as the cause. The diagnosis of bvFTD is corroborated by concordant frontal lobe atrophy on the MRI. |

Early Recognition At Primary Care

The two case studies illustrate how important it is to recognise atypical, non-amnestic symptoms of YOD. When assessing a patient with cognitive or behavioural symptoms (i.e., a neuropsychiatric syndrome), having a structured clinical approach helps.

1. COGNITIVE DOMAIN(S) AFFECTED

A systematic history-taking of the main cognitive domains may elucidate neuropsychiatric symptoms that suggest YOD. These domains are memory, executive function, visuospatial, language, apraxia and behavioural/psychiatric (Table 2).

If unexplained symptoms in one or more of these cognitive domains are detected, the GP should be alerted to suspect YOD even in the absence of memory symptoms that we typically associate with dementia.

| Cognitive Domain | Common Symptoms of Cognitive Impairment |

|---|---|

| Memory | • Repetitive questioning • Forgetting recent events or conversations • Forgetting things like their shopping list or location of parked car • Consistently misplacing items |

| Executive function | • Reduced attention span (e.g., absent-mindedness, difficulty following or holding conversation, distractibility) • Errors in judgement and making decisions • Difficulty with numbers or money • Rigidity in thought and habits |

| Visuospatial | • Difficulty judging movement (e.g., parking, driving, crossing the road) • Difficulty recognising objects, faces and landmarks by sight • Difficulty reading words |

| Language | • Expressive difficulties (e.g., word-finding difficulty [dysnomia], mispronunciation of words, agrammatism, distortion of speech) • Receptive difficulties (e.g., difficulty comprehending instructions, speech or words) • Repetition difficulties (e.g., difficulty repeating sentences) |

| Apraxia | • Difficulty performing learned tasks (e.g., using tools [telephone, computer, washing machine], cooking, dressing) |

| Behavioural or psychiatric | • Hyperactive symptoms: disinhibition, compulsive behaviour • Affective symptoms: anxiety, depression • Psychotic symptoms: delusions, hallucinations • Apathy • Change in eating habits |

Table 2 Common symptoms of cognitive impairment categorised by cognitive domain

2. TIME COURSE OF THE SYMPTOMS

In general, most neurodegenerative disorders follow an insidious time course.

However, unusual features such as rapid progression, fluctuations or a stepwise decline would warrant specialist referral particularly to look for reversible causes.

Rapidly progressive

For example, while rapidly progressive dementia is the hallmark of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease – an incurable and uniformly fatal neurodegenerative disorder – it can also occur in autoimmune encephalitis, a relatively common cause of YOD that may respond to immunotherapy.

Stepwise decline

A stepwise decline, likewise, would suggest vascular dementia and trigger a hunt for cerebrovascular disease, the treatment of which may prevent further strokes and arrest cognitive decline.

3. OTHER CLINICAL FEATURES

The presence of focal neurological deficits, seizures, Parkinsonism or movement disorders such as tremors or dystonia would warrant specialist referral.

In view of the higher likelihood of genetic predisposition in YOD compared to LOD, a family history of dementia or neuropsychiatric disorders in a young person with cognitive or behavioural symptoms would also raise the spectre of YOD.

Finally, a history of immunocompromised state, autoimmune diseases or uncontrolled cardiovascular risk factors may increase the likelihood of a treatable cause of YOD.

THE NNI DEMENTIA CLINIC |

|---|

At the NNI Dementia Clinic, patients with YOD undergo a comprehensive evaluation including a detailed history, neurological examination and neuropsychological assessment. Diagnosis Ancillary tests such as serology for autoimmune or infectious diseases, electroencephalography (EEG) or polysomnography (sleep study) may be performed for selected cases. Biomarker studies may be required for confirmation in atypical presentations of AD. These tests include cerebrospinal fluid examination for amyloid and tau protein, as well as amyloid PET imaging looking for cerebral amyloid deposition. Management A multifaceted approach is required, emphasising not only medical treatment with cognitive enhancers and cardiovascular risk factor management, but also psychological interventions for superimposed mood disorders, cognitive stimulation therapy and caregiver support. Equally important is the management of the social aspect of the disease, including its impact on employment, legal matters and financial planning. Last but not least, selected patients may also be eligible to participate in clinical trials, including that of disease-modifying therapy that may slow down progression of the disease. |

CONCLUSION

The heterogeneous nature of YOD often leads to delayed recognition and diagnosis. With an understanding of its unique features and a systematic clinical approach, GPs would be equipped to recognise and refer suspected patients at an early stage of the condition. Early diagnosis and treatment would be invaluable in improving the outcome of YOD.

REFERENCES

- Abbott A. Dementia: a problem for our age. Nature. 2011 Jul 13;475(7355):S2-4. doi: 10.1038/475S2a. PMID: 21760579.

- Kandiah N, Wang V, Lin X, Nyu MM, Lim L, Ng A, Hameed S, Wee HL. Cost Related to Dementia in the Young and the Impact of Etiological Subtype on Cost. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(2):277-85. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150471. PMID: 26444788.

- Mendez MF. Early-onset Alzheimer Disease and Its Variants. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019 Feb;25(1):34-51. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000687. PMID: 30707186; PMCID: PMC6538053.

- Lim L, Wong B, Vipin A, Silva E, Lim LLH, Chua EV, Choong TOC, Nyu MM, Chiew HJ, Hameed S, Ting SKS, Ng ASL, Ng KP, Kandiah N. Posterior cortical atrophy in Southeast Asia: Clinical andbiomarker profile. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2020;16(Suppl. 6):e044223. (POSTER PRESENTATION)

- Content of this article was adapted from course material for the 1st NNI Comprehensive Course in Dementia and Cognitive impairment (NNI-CCDC), NNI Dementia programme, 2019.

Dr Chiew Hui Jin is a Consultant at the Department of Neurology, National Neuroscience Institute (NNI). His interests are in neurocognition and medical education. He has been a member of the NNI Dementia Programme since 2017. He was the course director for the NNI Comprehensive Course in Dementia and Cognitive Impairment for primary care physicians in 2019.

GPs can call the SingHealth Duke-NUS Memory & Cognitive Disorder Centre for appointments at the following hotlines:

Singapore General Hospital: 6326 6060

Changi General Hospital: 6788 3003

Sengkang General Hospital: 6930 6000

National Neuroscience Institute: 6330 6363