By Dr Jasmine Chung, Infectious Disease Physician, SingHealth Duke-NUS Transplant Centre; Senior Consultant, Department of Infectious Diseases, Singapore General Hospital

The article is contributed/written by SingHealth Duke-NUS Transplant Centre

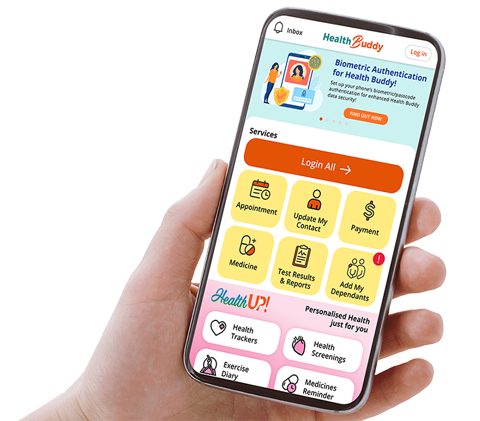

In kidney transplant recipients, common and uncomplicated infections can often be managed by general practitioners (GPs) – who are also in prime position to support them with safe living advice and vaccinations, and evaluate if escalation to a specialist is necessary. Find out more about the primary care management of this patient group.

KIDNEY TRANSPLANT IN SINGAPORE

Kidney failure is not uncommon in Singapore, and kidney transplant is by far the best means of treatment. It offers the patient the best survival advantage and a chance to lead a relatively normal life, with 5-year and 10-year overall survival rates of > 90% and > 80% respectively.1

Kidney transplant recipients constitute the largest proportion of solid organ transplant recipients in Singapore, with close to 2,000 patients still on active follow-up.2

POST-TRANSPLANT INFECTIONS

After the initial transplant surgery and a period of intense follow-up (usually a year), kidney transplant recipients would be stable on chronic immunosuppression, and seen at the transplant centre two to three times per year.

Often, evaluation and management of acute problems beyond their first year of transplant occur in the primary care setting.

Infections are common after kidney transplant; the epidemiology of infections varies depending on the post-transplant timeline.3

MITIGATING THE RISK OF POST-TRANSPLANT INFECTIONS

To reduce the morbidity and mortality of post-transplant infectious complications, most transplant centres would recommend the following4:

- Careful selection of patients for transplant

- Offer anti-infective prophylaxis, and/or surveillance where appropriate (e.g.,Pneumocystis jiroveci, cytomegalovirus, herpes virus prophylaxis), especially during the early post-transplant period and period of peak immunosuppression

- Recognise infectious disease syndromes, identify red flags and offer appropriate treatment in a timely fashion

- Keep transplant patients up-to-date with their routine adult vaccinations (including yearly influenza and COVID-19 vaccinations)

THE ROLE OF PRIMARY CARE IN MANAGING KIDNEY TRANSPLANT PATIENTS

There is an expanding pool of community dwelling, stable kidney transplant recipients living very active lives. Very often, common infections can be managed in primary care. Occasionally, patients may need to be referred to the transplant centre for further evaluation. For this group, good communication between primary care partners and the transplant teams is important to ensure seamless care and best outcomes.

To help determine the locus of care, see the summary table below and read on for more information.

HOW TO EVALUATE INFECTIONS IN THEKIDNEY TRANSPLANT RECIPIENT

Net state of immunosuppression

One key consideration in evaluating the kidney transplant recipient for infections is the patient’s ‘net state of immunosuppression’. Broadly speaking, it is a conceptual framework of all factors contributing to the infectious risk.5

In layman terms, it is:

- what type of immunosuppression,

- how much of it, and

- for how long

A ‘vintage’ kidney transplant recipient on years of immunosuppression would be considerably immunosuppressed.

A holistic approach

The types of infections that a kidney transplant recipient might acquire are a function of host factors and exposure history. The clinical syndrome and tempo of illness may help narrow the list of potential causative pathogens so that targeted investigations and empiric treatment may be instituted. See Figure 1.

COMMON INFECTIONS EVALUATED IN THE COMMUNITY IN KIDNEY TRANSPLANT RECIPIENTS

1. URINARY TRACT INFECTIONS

UTIs are common and account for approximately 50% of infectious com-plications in kidney transplant recipients.

The spectrum of illness includes asymptomatic bacteriuria, acute simple cystitis, complicated UTI (e.g., graft pyelonephritis/urosepsis), or recurrent UTI (≥ 3 UTIs in 12 months).6

Evaluation and management

There is now emerging data to recommend against routinely screening and treating asymptomatic bacteriuria in kidney transplant recipients, as this does not reduce the occurrences of symptomatic UTIs; instead, it increases unnecessary antibiotics use and selects for antibiotic-resistant infections.7 Routine screening and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria is not recommended beyond the first 1-2 months after transplantation.6

Collection of urine cultures is useful, especially for culture-directed therapy in an era where drug-resistant infections are increasingly common.

Routine test of cure is not recommended after the treatment of uncomplicated UTIs. If patients have non-resolving symptoms, they should be re-evaluated and worked up for drug-resistant/opportunistic infections, and non-infectious causes should be excluded.6

In patients with recurrent UTIs, it is important to exclude urinary retention, structural abnormalities, urinary reflux and prostatic abscesses in males, and consider physiological causes (e.g., atrophic vaginitis in post-menopausal women).

Long-term antibiotic prophylaxis is generally not recommended because of the selection of antibiotic-resistant infections; breakthrough infections are common.

Patients should be advised to maintain good personal hygiene, ensure good hydration and empty their bladder regularly.

Non-antibiotic prophylaxis (e.g., lactobacillus-containing probiotics, cranberry products, D-mannose, methenamine products) is sometimes used but the data supporting its use is limited.6

The duration of treatment for uncomplicated cystitis is 5-7 days, and longer for complicated UTI (approximately 14-21 days). Treatment duration may be extended if the response is slow.6

2. RESPIRATORY TRACT INFECTIONS

Respiratory tract infections are common perennially. The most common causes of respiratory tract infections are respiratory viruses which are often self-limiting. However, certain infections (e.g., influenza, respiratory syncytial virus [RSV] and COVID-19) are potentially severe and may be fatal. Prolonged viral shedding is not uncommon. Early antiviral therapy is often useful.8

Prevention

Prevention is key. Vaccination against common respiratory pathogens (e.g., influenza, COVID-19 and pneumococcal vaccination), and adhering to public health measures (avoiding crowded areas, performing hand hygiene and masking) is important.

3. DENGUE

Dengue is endemic in Singapore, and dengue infections may be more severe in transplant patients. The incidence of dengue with warning signs and severe dengue may be more common in patients on higher doses of steroids.10

In our local series, over 50% of patients had graft dysfunction at presentation, and this resolves with resolution of dengue.11 It is therefore important to pay attention to the patient’s fluid and hydration status during the evaluation.

Evaluation and management

For patients without warning signs and who can maintain adequate oral hydration, it is possible to manage them in the community.

However, close follow-up is required and early referral to the hospital is advised should there be signs of clinical deterioration.

4. DIARRHOEAL ILLNESSES

Patients may present with acute diarrhoea (< 14 days), persistent diarrhoea (14-29 days) or chronic diarrhoea (> 30 days). Again, the post-transplantation timeline, clinical history and exposure may allude to the possible causes.

Evaluation and management

Fever and bloody diarrhoea are signs of a more sinister process, and are concerning for infections with invasive enteropathogens or cytomegalovirus (CMV).

If symptoms are persistent, parasitic infections, viral infections (e.g., norovirus, CMV) and mycobacterial infections should be considered.

Stool examination (e.g., multiplex PCR, stool culture, C. diff toxin assay) to find out the causative pathogen is useful and targeted antimicrobial therapy can then be instituted.

It is also important to ensure adequate hydration so that graft function is preserved. Patients with signs of dehydration, dysentery or non-resolving symptoms need to be monitored closely to ensure that organ function is preserved, and more extensive workup (including endoscopic evaluation) may be warranted.

Diarrhoeal illnesses could also have non-infectious causes such as drugs (e.g., mycophenolate, calcineurin-inhibitors, diabetic medications, antibiotic-related), inflammatory bowel disease, malignancy and malabsorption syndromes. Keeping an open mind and timely referral for evaluation are important.9

SAFE LIVING

An ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure12

The goal of transplantation is to allow the patient to lead as normal a life as possible with a functioning graft.

While the risks of infections are higher than the general population, exposure can be reduced by:

Paying attention to water safety (clean water)

Paying attention to food safety: For example, avoiding raw/uncooked food, and avoiding food left out at room temperature fora prolon ged time.

Paying attention to animal and pet safety: For example, avoiding contact with animals during the period of maximal immunosuppression, practising good hand hygiene, avoiding exotic pets and having pets reviewed regularly by veterinarians.

Practising safe sex

Observing safety precautions during travels: Being aware of destination-specific vaccinations and medications that would be required for the trip is important. Advice can be sought from healthcare providers or travel health specialists 4-6 weeks prior to departure, where it is advisable to discuss any health concerns, your itinerary and planned activities. In addition, it is important to pack sufficient medications, plus extra in case travel delays occur.

Patients can also reduce their risk by adhering to other sensible infection prevention measures, which include:

Preventing infections transmitted by direct contact

The use of gloves where appropriate

Frequent and thorough handwashing before food preparation, eating and touching mucous membranes; before and after touching wounds; after touching pets/animals, gardening, changing diapers, touching secretions/excretions, and touching contaminated surfaces.

Preventing respiratory infections

Frequent and thorough handwashing

Avoiding contact with individuals with respiratory illnesses

Avoiding crowded areas

Avoiding tobacco smoke

Avoiding high-risk occupations (e.g., working in the construction/gardening/landscaping industries)

Avoiding plant/soil aerosols, chicken and other bird droppings

Vaccinations

Transplant recipients and their close contacts are advised to be up-to-date with their routine age-appropriate vaccinations.

CONCLUSION

The management of common and uncomplicated infections in the primary care setting is safe and beneficial for many kidney transplant recipients. Close collaboration between the primary care and transplant teams is important.

The primary care team can provide invaluable general medical advice, provide patient education, reinforce safe living advice and offer vaccinations to both transplant recipients and close contacts. GPs should escalate care in a timely and appropriate fashion if they have any particular concerns regarding a patient.

REFERENCES

Singapore General Hospital. Proceedings of Singapore Healthcare, 2012. 21(2): p. 95-101.

LiveOn Singapore. Singapore: Ministry of Health; 2024 Jun 30 [cited 2024 Nov 18]. Available from: https://www.liveon.gov.sg/resources.html.

Agrawal, A., M.G. Ison, and L. Danziger-Isakov, Long-Term Infectious Complications of Kidney Transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2022. 17(2): p. 286-295.

Briggs, J.D., Causes of death after renal transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 2001. 16(8): p. 1545-9.

Roberts, M.B. and J.A. Fishman, Immunosuppressive Agents and Infectious Risk in Transplantation: Managing the “Net State of Immunosuppression”. Clinical

Infectious Diseases, 2020. 73(7): p. e1302-e1317.

Goldman, J.D. and K. Julian, Urinary tract infections in solid organ transplant recipients: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant, 2019. 33(9): p. e13507.

Coussement, J., et al., Antibiotics versus no therapy in kidney transplant recipients with asymptomatic bacteriuria (BiRT): a pragmatic, multicentre, randomized, controlled trial. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2021. 27(3): p. 398-405.

Ison, M.G. and H.H. Hirsch, Community-Acquired Respiratory Viruses in Transplant Patients: Diversity, Impact, Unmet Clinical Needs. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2019. 32(4).

Angarone, M., D.R. Snydman, and A.I.C.o. Practice, Diagnosis and management of diarrhea in solid-organ transplant recipients: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant, 2019. 33(9): p. e13550.

Pinsai, S., et al., Epidemiology and outcomes of dengue in kidney transplant recipients: A 20-year retrospective analysis and comparative literature review. Clin Transplant, 2019. 33(1): p. e13458.

Tan, S.S.X., et al., Dengue virus infection among renal transplant recipients in Singapore: a 15-year, single-centre retrospective review. Singapore Med J, 2024. 65(4): p. 235-241.

Avery, R.K., M.G. Michaels, and A.S.T.I.D.C.o. Practice, Strategies for safe living following solid organ transplantation-Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant, 2019. 33(9): p. e13519.

Dr Jasmine Chung is a Senior Consultant with the Department of Infectious Diseases at Singapore General Hospital (SGH). She completed her specialist training in SGH and went on to do a one-year fellowship in transplant infectious diseases at Duke University Medical Centre in the United States of America. Since her return, she consults regularly in the transplant service and is currently serving as the Director of the Antimicrobial Stewardship Unit.

To find out more about our transplant programmes, GPs can contact the SingHealth Duke-NUS Transplant Centre or visit the website here.

Tel: 6312 2720

Email: sd.transplant.centre@singhealth.com.sg