When encountering facial paralysis, patients may first consult their general practitioner. As its impact is not only cosmetic but also functional and psychological, facial paralysis needs to be managed with care. We share how you can optimise care for these patients, from evaluation and grading to treatment.

INTRODUCTION TO FACIAL PALSY

Facial expressions are one of the most important non-verbal ways we communicate. Far from being a simple cosmetic issue, facial paralysis can result in significant functional and psychological consequences.

Bell’s palsy is the most common cause of facial paralysis. While early clinical trials of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines reported a very small number of post-vaccine Bell’s palsy cases, later studies found no association between the two.

In fact, according to recent research, the risk of Bell’s palsy seems to be higher for those who develop COVID-19 as compared to those who get the mRNA vaccine.

CAUSES OF FACIAL PALSY

The top differential causes of facial paralysis include idiopathic (Bell’s palsy), infectious (e.g., Ramsay Hunt syndrome) and tumours (central nervous system [CNS] / ear / parotid).

1. Bell’s palsy

The minimum diagnostic criteria are acute onset, ipsilateral lower motor neuron lesion and absence of other cranial, ear or parotid pathology. It is thus a diagnosis of exclusion.

It is postulated that herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) reactivation leads to compression at the meatal foramen from nerve swelling.

Progression to maximum weakness must occur within two days (less commonly, up to two weeks).

85% of patients start to recover by three weeks, achieving full recovery by six months without any specific intervention. The remaining 15% of patients have permanent diminished function (post-paralytic syndrome) and experience muscle weakness with synkinesis. Synkinesis refers to the unwanted co-contraction of different facial muscles (e.g., when the patient smiles, his eye closes involuntarily).

Risk factors include pregnancy and diabetes.

2. Ramsay Hunt syndrome

This is much less common than Bell’s palsy and is associated with herpes zoster reactivation. It is thus more common in the elderly and immunocompromised.

Symptoms may be more severe and may include cranial nerve (CN) VIII symptoms of hearing loss and giddiness. Vesicles may be seen on the pinna, external auditory canal, palate or tongue.

The prognosis is worse than Bell's palsy with 50-70% of patients achieving complete recovery.

3. Other infective causes

- These may include cholesteatoma, otitis media, HIV infection and Lyme disease, etc.

4. Tumours

- Tumours arising in the CNS (acoustic neuroma), tumours along the course of the nerve itself (facial nerve schwannoma) and parotid tumours can present with facial paralysis developing over a few weeks to months.

5. Congenital

- Developmental causes or birth trauma can result in facial paralysis.

How to Optimise Management in Primary Care |

|---|

Bell’s palsy, with its acute presentation, is commonly misdiagnosed by the layman as a stroke. Patients thus commonly present to the accident and emergency department. However, some patients may consult their general practitioner first. EVALUATION AND GRADINGEvaluation begins with careful history-taking regarding comorbidities, onset, duration, previous episodes and associated symptoms (e.g., vertigo, hearing loss, otalgia and otorrhoea). Clinical examination should include the cranial nerves to determine if this is an isolated CN VII palsy or if there are multiple CN palsies, as well as to establish if it is an upper or lower motor neuron lesion. Carry out a complete head and neck examination of the ear, parotid gland, neck and intraorally. Finally, grade the severity of the palsy based on the House-Brackmann system. TREATMENT OPTIONS BY GPsPrimary care treatment consists of the following: 1. Eye care

2. Steroids (the mainstay of treatment for Bell’s palsy)

3. Antivirals (in addition to steroids, not alone)

4. Facial neuromuscular retraining

WHO SHOULD BE REFERRED TO A SPECIALISTThe following patients should be referred to an ENT specialist for workup, as well as the facial nerve clinic for facial reanimation options:

|

ADVANCES IN TREATMENT OPTIONS

Facial neuromuscular retraining (NMR)

There are 42 individual facial muscles, innervated by five separate facial nerve branches and capable of making more than 10,000 expressions.

Non-specific general therapies used for injuries to other body parts (such as gross strengthening and electrical stimulation) should not be applied to the face.

The focus is on improving coordination between muscles as opposed to simply increasing their strength. Using a tailor-made retraining programme will induce long-term improvement by the process of brain plasticity. At Singapore General Hospital (SGH), our speech therapists are specially trained in facial NMR and work with all types of facial nerve conditions.

Medical

Botulinum toxin injection (BOTOX®) is an important adjunct in the treatment of facial nerve disorders. It prevents the release of acetylcholine across the neuromuscular junction, causing selective paralysis of involuntarily contracting muscles around the eyes and mouth.

It relieves muscle tightness and spasms in longstanding post-paralytic syndrome. It is also a nonsurgical treatment for conditions such as blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm.

BOTOX® effects can last four to six months and over time, injections can be given at a reduced frequency of one to two years if facial NMR is also carried out. BOTOX® injections for such medical indications are affordable and MediSave/insurance claimable.

Surgical

Surgery for facial palsy

Surgical treatment is aimed at the holistic restoration of the droopy brow, eye exposure and smile paralysis and is MediSave/insurance claimable.

Before one year, the facial muscles are still viable and the connection of new neural input by means of nerve grafting from the contralateral facial nerve / ipsilateral masseter nerve can allow dynamic smiling and eye closure.

In chronic palsy, facial muscles undergo irreversible atrophy and another muscle (e.g., temporalis muscle or a slip of latissimus dorsi muscle) can be used for smile reanimation.

Ancillary procedures such as brow lifts enable the restoration of brow position and prevent obstruction of the visual axis. Lower eyelid tightening procedures with the addition of a platinum weight into the upper eyelid can help the eye to close.

Surgery for post-paralytic syndrome

This consists of selective myectomies or neurectomies of overactive antagonist facial muscles to enable rebalancing of the smile and eye closure.

THE FACIAL NERVE CLINIC AT SINGAPORE GENERAL HOSPITAL |

|---|

The SGH Facial Nerve Clinic run by Dr Wong Manzhi was launched in 2016. It is conveniently sited within the ENT Centre on Wednesday mornings, and aims to provide one-stop clinical care for both subsidised and private patients. We manage patients presenting with all types of acute and chronic facial nerve conditions, providing investigations and holistic management of eye, smile and face issues. In association with specially-trained speech therapists, facial neuromuscular retraining is carried out in addition to medical and surgical treatment. |

Dr Wong Manzhi is a Senior Consultant Plastic Surgeon at Singapore General Hospital (SGH). In addition to all facets of reconstructive and aesthetic surgery, she is one of the few doctors in Singapore who have expertise in the sub-specialty management of facial nerve conditions.

She underwent a year-long operating fellowship at Kyorin University Hospital, Japan, which sees the highest number of patients with facial nerve disorders in Japan. Upon her return, she started the Facial Nerve Clinic located within the Ear, Nose and Throat Centre at SGH and a similar clinic in Tan Tock Seng Hospital. She is also a Visiting Consultant at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital.

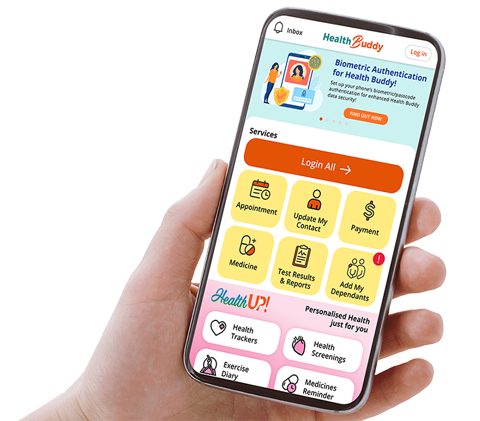

GP Appointment Hotline: 6326 6060

GPs can scan visit the website for more information about the department.