General practitioners are at the core of diabetes care, risk factor modification and complication monitoring. When it comes to diabetes foot complications, the stakes are high and thus need to be carefully managed. The SingHealth Duke-NUS Diabetes Centre shares tips on primary care treatment and when referral to a specialist is needed.

THE DIABETES FOOT IN SINGAPORE

Prevalence

Lower limb amputations are one of the most feared diabetes co mplications and unfortunately, Singapore has one of the highest amputation rates in the developed world1.

Diabetes mellitus affects approximately one in six adults between 21 and 69 years of age in Singapore, but the lifetime risk is projected to reach one in every two adults by 2050.2

The lifetime risk of developing a foot ulcer ranges from 15% to 25% of those with diabetes, while foot ulcers precede 80% of all lower limb amputations in those with diabetes.3

Risk factors

The risk factors for developing a foot ulcer and lower limb amputation are well-established in Singapore.4

In addition to traditional cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., dyslipidaemia, hypertension, smoking and poorly controlled diabetes), a younger age at diagnosis (longer duration of diabetes) and those with chronic kidney disease are at the highest risk of diabetes foot complications.

Diabetes foot problems make up a large proportion of all hospital days due to diabetes, but integrated diabetes foot pathways with early access to care can significantly reduce the morbidity associated with diabetes foot disease.3

CASE STUDY |

|---|

Patient background Ms F is 53-year-old Malay ex-smoker working as a store attendant. She was noted to have a painless right foot callus during her regular review with her general practitioner (GP). She has had type 2 diabetes for 12 years, complicated by mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy bilaterally, chronic kidney disease and peripheral neuropathy noted on a diabetes foot screen four years ago. She failed to attend regular diabetes foot screening as she did not see its value. Symptoms Ms F noticed a painless red discolouration around a callus that had formed over the base of her right foot under the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. The callus was ascribed to her recent change in footwear and had progressively darkened over the preceding week. She was pain-free and did not restrict her activities. She did not wish to miss time at work, and thus only consulted her primary care team six days later at her scheduled chronic disease review. Presentation At presentation to her GP, there was a fluctuant callus on the dorsal aspect of the first MTP on the right. She had fallen arches bilaterally with poor nail hygiene. She also had weak but palpable pulses bipedally, and absent sensation up to the medial malleolus bilaterally when assessed using a 10 g monofilament. The tissue surrounding the callus was erythematous and warm, but she was apyrexic without signs of systemic infection or joint involvement.

Clinical course Ms F was treated with oral co-amoxiclav, advised to avoid weight bearing on the foot and was referred to the Rapid Access FooT (RAFT) Clinic at Singapore General Hospital (SGH). Initial review and education She was reviewed by the vascular, podiatry and diabetes teams three days later.

Her atheromatous changes were distal and there was not any focal proximal arterial stenosis noted on imaging to merit considering revascularisation options. Some misconceptions about the role of regular foot screening were addressed in addition to giving guidance on wound care and dressings. Ms F and her family were educated regarding appropriate footwear, the red flags / warning signs to look out for and what actions to take if concerned.

Follow-up review and recovery Her employer allowed her to take sufficient time off work to facilitate wound healing and she was also able to perform her duties while seated when she returned to work. Her wound healed well after five weeks with regular podiatry review and wound dressings. Her statin therapy was changed to a more potent statin to achieve an LDL under 1.8 mmol/L, and she commenced a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor (SGLT2i) after her wound healed to address her CKD with microalbuminuria, raised BMI and suboptimal glycaemic control. Her LDL and HbA1c had both improved three months later when reviewed by her primary care team. She was advised that while her wound was ‘healed’, the recurrence rate within one to five years is extraordinarily high, and she will remain in the highest risk group for developing a future foot ulcer. |

TREATMENT OPTIONS BY GPs

The key initial approach is to:

- Offload the foot

- Treat any underlying infection

- Consider local treatments to accelerate healing

- Escalate care if necessary

GPs can consult the Appropriate Care Guide5 by the Agency for Care Effectiveness when assessing an individual's risk of diabetes foot complications.

Table 2 outlines the various assessment and treatment options available.

An experienced wound nurse and podiatrist are invaluable when considering local treatments and choosing the most appropriate dressings and footwear for acute diabetes foot injuries.

Often, patients presenting with an acute foot ulcer have been infrequent attenders to the clinic. Many have poorly controlled cardiovascular risk factors or have missed screening for other diabetes complications, and this represents an opportunity to re-engage the patient.

Diabetes Foot Ulcer Assessment and Treatment | |

|---|---|

Initial assessment and reassessment |

|

Local treatments |

|

Infection treatment |

|

Education |

|

Offload |

|

Revascularisation / Surgery |

|

Opportunistic diabetes complications and cardiovascular risk factor screening | |

WHEN GPs SHOULD REFER A PATIENT

Referral to the emergency department

Signs or symptoms of acutely ischaemic foot or evidence of systemic infection due to a foot infection should prompt immediate referral to the emergency department.

Referral to a diabetes foot specialist

A new ulcer, any tissue loss or foot infection in patients at higher risk should prompt early review by a diabetes foot specialist.

Even those at lower risk with wounds that worsen at any stage of treatment or fail to improve after four weeks of initial therapy should also be referred.

Those with intermittent claudication or rest pain should be seen early by a vascular surgeon.

Absent or reduced pulses and lower ankle brachial index (ABI) scores without tissue loss are common findings. If these are noted in those without symptoms or tissue loss, invariably, early specialist review is unnecessary.

Rapid access clinics

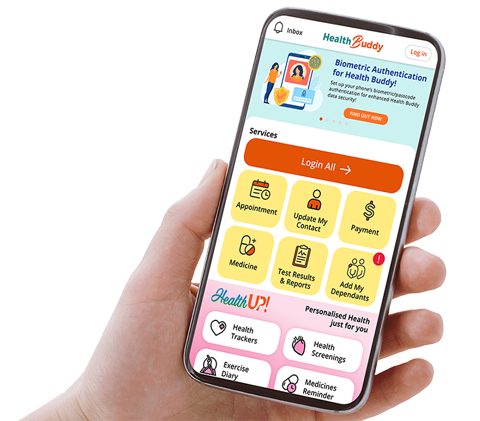

There is an array of rapid access clinics available with the appropriate option dependent on the physician’s level of concern and the primary complaint.

In SGH, patients like Ms F can be referred to the:

Rapid Access FooT (RAFT) Clinic

Rapid Access Vascular Clinic

Diabetes Fast Track Clinic

Similar services are available in Sengkang Hospital and Changi General Hospital.

TREATMENT OPTIONS BY SPECIALISTS

The main advantage of a dedicated diabetes foot clinic is the coordination of investigations and care with multidisciplinary input on treatment decisions.

These clinics reduce the number of hospital visits for patients and have repeatedly been shown to reduce the morbidity associated with diabetes foot disease.3

Revascularisation, skin grafting and foot deformity corrective surgery are some of the surgical options available in addition to surgical debridement, and major or minor lower extremity amputation.

REASSESSMENT AND FOLLOW-UP

Continued monitoring and timely referrals

Diabetes care, risk factor modification and complication monitoring should be centred in primary care for the majority of patients.

Those with a history of foot ulcers will remain at high risk of recurrence. Therefore, four-to-six-monthly foot assessments augmenting the patients’ and carers’ daily examination of the patients’ feet are necessary.

Rapid access to a multidisciplinary team assessment when necessary can reduce the need for lower extremity amputations.

Improving patient education

Each touchpoint in clinics and hospitals is an opportunity to improve patient knowledge. We have demonstrated that a collaborative approach in patient education can yield a greater increase in knowledge retention and self-care behaviours.6

Giving patients the tools to recognise diabetes foot problems and the appropriate actions to take are key factors in reducing morbidity in Singapore.

Lower health literacy in older patients, challenges around missing work and fear of amputations are some of the common reasons observed for delayed presentation with an acute diabetes foot problem in Singapore. This can be minimised through coordinated care, regular screening and targeted education.

REFERENCES

Riandini T, Pang D, Toh MPHS, Tan CS, Choong AMTL, Lo ZJ, Chandrasekar S, Tai ES, Tan KB, Venkataraman K. National Rates of Lower Extremity Amputation in People With and Without Diabetes in a Multi-Ethnic Asian Population: a Ten Year Study in Singapore. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2022 Jan;63(1):147-155. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2021.09.041. Epub 2021 Dec 14. PMID: 34916107.

Phan TP, Alkema L, Tai ES, et al. Forecasting the burden of type 2 diabetes in Singapore using a demographic epidemiological model of Singapore. BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care 2014;2:e000012. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2013-000012

Armstrong DG, Boulton AJM, Bus SA. Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Recurrence. N Engl J Med. 2017 Jun 15;376(24):2367-2375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1615439. PMID: 28614678.

Yang Y, Østbye T, Tan SB, Abdul Salam ZH, Ong BC, Yang KS. Risk factors for lower extremity amputation among patients with diabetes in Singapore. J Diabetes Complications. 2011 Nov-Dec;25(6):382-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2011.08.002. Epub 2011 Oct 7. PMID: 21983153.

Agency for Care Effectiveness. Foot assessment in people with diabetes mellitus. Retrieved 28 November 2022, from https://www.ace-hta.gov.sg/healthcare-professionals/ace-clinical-guidances-(acgs)/details/foot-assessment-in-people-with-diabetes-mellitus

Heng ML, Kwan YH, Ilya N, Ishak IA, Jin PH, Hogan D, Carmody D. A collaborative approach in patient education for diabetes foot and wound care: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Int Wound J. 2020 Dec;17(6):1678-1686. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13450. Epub 2020 Jul 29. PMID: 32729231; PMCID: PMC7949298.

Ng N. Understanding Diabetes and chronic limb-threatening ischaemia. SingHealth Defining Med. Retrieved 28 November 2022, from https://www.singhealth.com.sg/news/defining-med/chronic-limb-threatening-ischaemia

Dr David Carmody is an Endocrinologist based at Singapore General Hospital. He is the lead endocrinologist in the hospital’s Rapid Access FooT clinic. Dr Carmody graduated with an MB BCh BAO (Honours) from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) in 2004. He completed his advanced specialist training in both internal medicine and endocrinology through the Royal College of Physicians in Ireland in 2016. He was awarded his postgraduate research degree (MD) in 2017 by RCSI. His current clinical and research interests focus primarily on atypical forms of diabetes mellitus and complications of diabetes mellitus.

GPs can call the SingHealth Duke-NUS Diabetes Centre for appointments at the following hotlines:

Singapore General Hospital: 6326 6060

Changi General Hospital: 6788 3003

Sengkang General Hospital: 6930 6000

KK Women's and Children's Hospital: 6692 2984

Singapore National Eye Centre: 6322 9399