While certain small vascular tumours and malformations can be well-managed in the primary care setting, more complex and severe cases would greatly benefit from a multidisciplinary specialty care approach. Read more about how the vascular anomalies teams at the SingHealth Duke-NUS Vascular Centre can help to manage these patients, utilising multimodal treatment for optimal outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Vascular anomalies are a heterogeneous group of conditions that involve abnormal growth or arrangement of various forms of blood or lymphatic vessels in the body. They can range from mild to severe conditions that can lead to significant physical, psychological and emotional impairment.

Small infantile haemangiomas or capillary malformations, especially those not on critical sites (e.g., arms, legs and trunk) can be managed in the primary care setting.

However, more complex and severe vascular anomalies should ideally be managed under the care of a multidisciplinary team in centres specialising in their management. A combination of various treatments involving input from various sub-specialties may be required for optimal results.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY MANAGEMENT OF COMPLICATED VASCULAR ANOMALIES FOR BETTER OUTCOMES

Complex and complicated vascular anomalies require multimodal and multidisciplinary management to optimise outcomes.

Typical treatment modalities include:

- Systemic medications

- Interventional radiological procedures (e.g., sclerotherapy and embolisation)

- Surgery

- Lasers

- Physical therapy

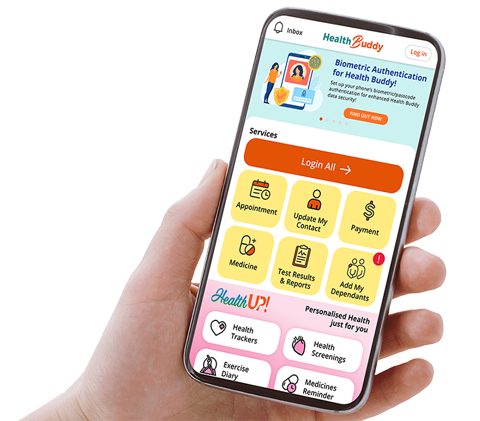

The multidisciplinary vascular anomalies teams at KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital (KKH) and Singapore General Hospital (SGH) are part of the SingHealth Duke-NUS Vascular Centre (SDVC), and provide a one-stop centre for the diagnosis and management of a wide range of vascular anomalies in adults (seen at SGH) and children and adolescents (seen at KKH).

The teams comprise experts in the fields of:

- Dermatology

- Interventional radiology

- Haematology/oncology

- Plastic and reconstructive surgery

- Paediatric surgery

- Vascular surgery

- Orthopaedic surgery

- Genetics

- Gastroenterology

- Respiratory

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology

- Physiotherapy

- Occupational therapy

- Speech and language therapy

- Psychology

CASE STUDY: The Multidisciplinary Management of a Young Woman with Extensive Venous Malformations |

|---|

Initial presentation and history Patient M presented to the Vascular Anomalies Clinic at KKH with extensive venous malformations of her lip, tongue and buccal mucosa (Figure 1A). These were present at birth and had gradually increased in size over the years. Imaging revealed deeper involvement including the pharynx and larynx, with narrowing of her upper airways. While the patient had previously sought advice from other healthcare providers, no single treatment had been deemed effective and safe due to the extent of airway involvement. A multidisciplinary management plan With discussion amongst the members of the multidisciplinary vascular anomalies team at KKH, a targeted and holistic management plan was put in place for the patient. This involved multimodal treatment with oral sirolimus, multiple treatment sessions for sclerotherapy, and pulsed dye laser (PDL) and neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Nd:YAG) laser treatment over two to three years. She was under continued review by the multidisciplinary teams at both KKH and SGH. Patient outcomes Post-treatment, there was marked improvement in the size of the venous malformations, both externally and internally (Figure 1B). The patient and her family were happy with the results, and she is now a more confident young woman. M continues to be reviewed by her multidisciplinary care team.  Figure 1 Venous malformations affecting the tongue, lip and larynx, before (A) and after (B) multimodal treatment |

CLASSIFICATION OF VASCULAR ANOMALIES

According to the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA), vascular anomalies can be classified into two broad categories – vascular tumours and vascular malformations (Figure 2). This classification has led to standardisation of the nomenclature. This is important as there now exists a variety of treatment options targeted at the various vascular tumours and malformations. Accurate diagnosis is key for appropriate treatments and optimal outcomes.

Figure 2 ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies 2018 (abridged)

CM: capillary malformation, VM: venous malformation, LM: lymphatic malformation, AVM: arteriovenous malformation

TYPES OF VASCULAR ANOMALIES AND THEIR TREATMENT

VASCULAR TUMOURS

1. INFANTILE HAEMANGIOMAS

Infantile haemangiomas (IH) are a type of vascular tumour that presents in the first three to four weeks of life as enlarging red or bluish papules or nodules (Figure 3). They grow in breadth and depth over four to five months and thereafter, they slow in growth until the child is about a year old before beginning to involute.

IHs are the most common vascular tumours in children, affecting 2-4% of infants. They are more common in females, premature infants and twins.

Complications

Most IHs are uncomplicated with minimal cosmetic concern and can be observed for spontaneous resolution. Small IHs can involute to nearnormal skin. Large IHs, however, if left untreated, may involute with residual fibrofatty change, telangiectasia and skin atrophy.

A handful of IHs may lead to life-threatening or function-threatening complications or have the potential to cause severe cosmetic disfigurement.

Complicated IHs require prompt referral to a specialist centre, as early treatment within the first six months of life can reduce the following complications:

- Large IHs on the head and neck region may be associated with eye, brain and heart abnormalities (PHACE syndrome), while those in the groin, perineal or sacral region may be associated with spinal and genitourinary abnormalities (PELVIS syndrome)

- IHs at certain sites (e.g., lip, groin, neck and ear) may ulcerate and lead to pain, infection and scarring

- Multiple IHs (five or more) may be associated with visceral involvement (e.g., liver or spleen) and consumptive hypothyroidism

Treatment

Both systemic (e.g., propranolol) and topical (e.g., timolol) beta-blockers have been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of complicated IHs if started within the first year of life.

Lasers, such as PDL, can also be used to treat IHs.

Occasionally, reconstructive surgery may be required for large, pedunculated IHs or for treatment of residual cosmetic concerns. Radiological interventions such as embolisation may be required for large visceral IHs that are associated with high-output cardiac failure.

2. KASABACH-MERRITT SYNDROME, KAPOSIFORM HAEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA AND TUFTED ANGIOMA

Kasabach-Merritt syndrome (KMS) is characterised by thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy and microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, and can lead to severe bleeding in a child due to low platelets and clotting factors.

The syndrome is associated with a rapidly expanding kaposiform haemangioendothelioma (KHE) (Figure 4) and tufted angioma (TA), which are uncommon vascular tumours presenting in infancy.

The vascular lesion commonly becomes enlarged and indurated, and infants can present with bleeding manifestations such as ecchymoses, epistaxis, haematochezia and haematuria.

Diagnosis

Although both KHE and TA can be locally aggressive, they may also undergo spontaneous involution. Diagnosis of KHE and TA is made based on clinical, radiological (ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) and histological features.

Treatment

Treatment of KMS, KHE and TA may require different regimens and a multidisciplinary approach.

Management options include systemic high-dose corticosteroids, antifibrinolytics, interferons, vincristine and antithrombotics.

More recently, the use of mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitors has proven to be effective in reducing both KMS as well as the size of the underlying tumour. Surgery, embolisation and radiation may also be occasionally required.

VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

1. CAPILLARY MALFORMATIONS / PORT-WINE STAINS

Capillary malformations or port-wine stains (PWS) initially appear flat (Figure 5) but may thicken and appear hypertrophic during adulthood. The commonest form of vascular malformations, they usually present at birth and grow in proportion to the child.

Complications

Certain PWS may result in significant cosmetic disfigurement. Pyogenic granuloma-like lesions that lead to recurrent bleeding can also develop.

Large PWS affecting the forehead or eyelids may be associated with Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS), with cranial and ophthalmological associations. These patients require brain imaging and regular eye examinations. Seizures and developmental delays are common neurological manifestations of SWS.

Treatment

PWS can be treated with lasers such as PDL or Nd:YAG laser. Treatments can begin within the first few months of life and require multiple sessions, usually one to two months apart.

Hypertrophic PWS may require reconstructive surgery or interventional ablation.

2. VENOUS AND LYMPHATIC MALFORMATIONS

The next most common forms of vascular malformations, venous and lymphatic malformations, appear as soft, bluish-to-purplish swellings (Figure 6).

They usually present within the first few years of life but can also become prominent during puberty, or less commonly, in adulthood.

Diagnosis

Although mostly asymptomatic, they can present with pain, bleeding, thrombosis and secondary infection. Diagnosis is made on clinical, radiological (e.g., ultrasound and MRI) and occasionally, histological features.

Recently, an increasing number of somatic genetic mutations have been discovered in these vascular anomalies (e.g., PIK3CA). Genetic testing may be offered in some cases to guide management.

Treatment

Small, asymptomatic lesions may be left alone, while treatment is recommended for larger lesions, especially if symptomatic. Various treatment modalities are often combined for optimal results, including systemic medications (e.g., mTOR or PIK3CA inhibitors), sclerotherapy, lasers and surgery.

3. VASCULAR MALFORMATION SYNDROMES

Some vascular malformations may be associated with other abnormalities, such as tissue overgrowth, bony and visceral involvement, soft tissue tumours and epidermal nevi. These ‘vascular malformations syndromes’ are rare but have the potential to lead to severe physical and psychosocial impairment.

Somatic mosaic mutations in PIK3CA have been found in the PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS). These include Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome (Figure 7) and congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, epidermal nevi and scoliosis/skeletal/spinal anomalies (CLOVES) syndrome. Patients with PROS present with asymmetric limb overgrowth associated with various slow-flow vascular malformations.

Treatment

Multimodal and multidisciplinary treatment is required for these patients, including sclerotherapy, embolisation, systemic medications (e.g., mTOR and PIK3CA inhibitors), lasers and surgery.

CONCLUSION

Vascular anomalies comprise vascular tumours and vascular malformations. They commonly present in childhood but can also occur in adolescents and adults.

The ISSVA classification has provided a basis for accurate and timely diagnosis of vascular anomalies. Accurate diagnosis is of paramount importance in deciding on the management of these patients.

Complicated vascular anomalies should be diagnosed and managed by a multidisciplinary vascular anomalies team, utilising multimodal treatment for optimal treatment outcomes.

REFERENCES

- ISSVA classification for vascular anomalies (2018). Retrieved from https://www.issva.org/UserFiles/file/ISSVA-Classification-2018.pdf

- Harter N, Mancini AJ. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangiomas in the neonate. Pediatr Clin North Am 2019; 66:437-459

- Hammill AM, et al. Sirolimus for the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011; 57:1018-1024

- Zuniga-Castillo M, Teng CL, Teng JMC. Genetics of vascular malformation and therapeutic implications. Curr Opin Pediatr 2019; 31:498-508

- Martinez-Lopez A, et al. Vascular malformations syndromes: an update. Curr Opin Pediatr 2019; 31:747-753

Clin Assoc Prof Mark Koh Jean Aan

Service Chief @ KKH, SingHealth Duke-NUS Vascular Centre;

Head & Senior Consultant, Department of Dermatology,

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital

Clinical Associate Professor Koh is a dermatologist who specialises in paediatric dermatology and dermatopathology. He is also a visiting consultant at Singapore General Hospital, Sengkang General Hospital and the National Cancer Centre Singapore. He is a Clinical Associate Professor at Duke-NUS Medical School; Adjunct Associate Professor at the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University; and Senior Clinical Lecturer at the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Dr Luke Toh Han Wei

Senior Consultant, SingHealth Duke-NUS Vascular Centre;

Head, Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging;

Interventional Services, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital

Dr Luke Toh received his fellowship training in paediatric interventional radiology, and is a diagnostic radiologist with special interest in the management of vascular malformations. He also a visiting consultant at Singapore General Hospital. Dr Toh is a Clinical Assistant Professor at Duke-NUS Medical School and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the Department of Anatomy, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore.

Clin Assoc Prof Chan Mei Yoke

Senior Consultant, SingHealth Duke-NUS Vascular Centre;

Haematology/Oncology Service, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital

Clinical Associate Professor Chan Mei Yoke is a paediatric haematologist/oncologist and palliative care specialist. She trained at the Vascular Anomalies Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, USA and contributed to the development of the multidisciplinary Vascular Anomalies Clinics at KK Women's and Children's Hospital and Singapore General Hospital. She is a Clinical Associate Professor with Duke-NUS Medical School; Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore; and Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine, Nanyang Technological University.

GPs can call the SingHealth Duke-NUS Vascular Centre for appointments at the following hotlines:

Singapore General Hospital: 6326 6060

Changi General Hospital: 6788 3003

Sengkang General Hospital: 6930 6000

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital: 6294 4050

National Heart Centre Singapore: 6704 2222