With the increased survival rates following CAR T-cell therapy, more patients are returning to the care of their general practitioner (GP). The SingHealth Duke-NUS Blood Cancer Centre lays out the potential late effects of treatment, and how GPs can effectively support and co-manage these patients, with timely referral where necessary.

INTRODUCTION TO CAR T-CELL THERAPY

A growing population of patients with B-cell haematological malignancies have undergone chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy following the approval of two CAR T-cell therapies (tisagenlecleucel and axicabtagene ciloleucel) in Singapore.

Positive patient outcomes

Adults with relapsed and/or refractory (R/R) lymphoma

Complete response (CR) rates of 40-54% and durable response rates of 30-40% have been reported at four-year follow-up.1,2

These outcomes are noteworthy considering that data from patients with R/R diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with conventional chemotherapy and autologous transplant showed CR rates of 7%, and median overall survival of only 6.3 months.3

Young adult patients with R/R B-acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

Improved responses were noted with CR rates of 81% and durable responses of 76% at 12 months.4

Expanding knowledge of side effects

While the acute toxicities of CAR T-cell therapy including cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) are well defined, data regarding late adverse effects are also now increasingly recognised.

Aside from the notable late side effects including cytopenia, B-cell aplasia and hypogammaglobulinemia, others including neuropsychological impact and secondary malignancies are recognised more and more today.

In this article, we will describe the established and potential late effects of CAR T-cell therapy and discuss management from the primary care perspective.

As more CAR T-cell recipients transition back to the community, continued close communication between general practitioners (GPs) and specialist CAR T centres will be important to improve understanding of treatment late effects and optimise comanagement.

Long-Term Late Effects of CAR T-Cell Therapy

1. B-CELL DEPLETION AND HYPOGAMMAGLOBULINEMIA

Long-lasting B-cell depletion following anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy is common, related to the ontarget, off-tumour effects of CAR T-cell therapy, and is associated with an increased risk of infection.

Hypogammaglobulinemia occurs due to impaired B-cell and plasma cell activity and can persist several years after infusion.

Risk factors

The risk of hypogammaglobulinemia is higher in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia who are treated with tisagenlecleucel, but lower in non-Hodgkin lymphoma.4

Management

Immunoglobulin replacement is commonly continued in patients with immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentration of less than 400 mg/dL or recurrent infections until B-cell recovery.

While an impaired response to vaccines has been observed, we continue to recommend vaccinations after CAR T-cell therapy to reduce infection risk and treatment-related morbidity and mortality.

At three months post-therapy, CAR T-cell recipients will begin the recommended schedule for vaccinations, including for COVID-19.

Despite completing COVID-19 vaccinations, patients should be advised to continue exercising precautions to reduce their risk of SARS-CoV-2 exposure and infection (e.g., mask wearing, physical distancing, avoiding crowds and poorly ventilated spaces).

While intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) therapy does not inhibit immune responses for inactivated vaccines, MMR and varicella vaccines should be administered at least two weeks before receipt of IVIg, and should be delayed by eight months after receipt of IVIg.

Live and non-live adjuvant vaccines can be considered one year after CAR T-cell therapy.5

2. LATE INFECTIONS

Patients treated with CAR T-cell therapy are at increased risk for infections. In approval trials for tisagenlecleucel and axicabtagene ciloleucel (JULIET and ZUMA-1 respectively), grade three or higher infections occurred at a rate of 18% beyond eight weeks, and at 8% beyond six months.1,2

Due to continued B-cell aplasia and hypogammaglobulinemia, infection remains the leading cause of non-relapse mortality after CAR T-cell therapy.7

Risk factors

Factors associated with infection include the occurrence of severe acute toxicities such as CRS and ICANS, which require the use of high-dose steroids, anti-interleukin-6 (tocilizumab) and antiinterleukin-1 (anakinra) treatment during the first month after CAR T-cell infusion.8

Management

The most common site of late infection is respiratory, and the most common aetiology is viral, followed by bacterial and fungal.9 Late reactivation of herpetic and zoster infection have also been reported and extended-duration acyclovir prophylaxis is recommended.

Similarly, pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis is recommended for six to 12 months or until the CD4 count is greater than 400 cells/μL5.

3. PROLONGED CYTOPENIA

Chronic cytopenias, including anaemia, thrombocytopaenia and neutropaenia, can last more than three months after CAR T-cell infusion in about 15% of CAR T-cell recipients.6

Risk factors

The risk of cytopenias is associated with:

Higher-grade CRS

Multiple previous lines of therapy

Receipt of allogeneic transplant within a year prior to CAR T-cell infusion

Baseline cytopenia

The presence of lymphoma or leukaemia in the bone marrow affecting marrow reserves

Management

Chronic cytopenias may need:

Transfusion support

Filgrastim

Thrombopoietin receptor agonists (eltrombopag)

Epoetin support

In general, prolonged cytopenia is expected to gradually recover even without intervention. Vigilance should be maintained for alternative explanations for cytopenia, such as relapsed disease in the marrow and secondary myeloid malignancies. The underlying mechanism of prolonged cytopenia after CAR T-cell therapy remains elusive and active research is ongoing, which may lead to more specific treatments in the future.

4. POTENTIAL ORGAN-SPECIFIC TOXICITIES

Cardiac toxicities including cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias and heart failure have been reported after CAR T-cell trials at rates of 29-39%.15 Cardiac effects are likely related to interleukin 6.

Among patients with grade two or higher CRS, arrhythmias occurred in 12% and new-onset heart failure occurred in 11%, with death occurring in 6%. In patients with grade three or higher CRS, the rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and newonset cardiomyopathy incidence were even higher.

Risk factors

This risk of cardiac toxicities is increased in patients with high disease burden, older age and pre-existing cardiovascular disease.

Management

In patients who present to primary care with new onset breathlessness and decreased effort tolerance, proper referral for formal cardiac evaluation should be considered.

5. FATIGUE

Fatigue was common among patients in the ZUMA-1 trial and was found to be difficult to manage.16 While fatigue generally improves between four to six weeks after CAR T-cell infusion, some patients continue to be affected for months post-treatment.

Management

Steroids should be avoided in these patients. Some patients may need physical therapy to regain strength, stamina and stability. Daily exercises such as walks can help build stamina and strength. Other interventions to manage fatigue may include exercise, yoga, meditation, pilates and massages.

Patients should be reminded that driving a car or operating heavy machinery is not recommended for eight weeks after CAR T-cell therapy due to the risk of sleepiness, confusion, weakness or temporary memory and coordination problems after CAR T-cell therapy.

6. NEUROLOGICAL TOXICITIES

Neuropsychological late effects

The long-term neurocognitive effects in patients experiencing neurotoxicity have yet to be established fully and is an active area of research.7

In a retrospective study of 86 patients, late-onset neurologic findings occurred in 10% of patients. These neuropsychological late effects included:

Cerebrovascular accidents

Transient ischaemic attacks

Peripheral neuropathy

Alzheimer’s disease

Depression

Anxiety

Additionally, ongoing memory impairment three weeks post-infusion has also been reported in 4–5% of CAR T-cell recipients.4

Risk factors

Young age, pre-existing anxiety and depression, and acute neurotoxicity were associated with an increased likelihood of long-term neurocognitive effects.14

Management

In view of the risk of long-term neurocognitive effects after CAR T-cell therapy, especially for those who had acute neurotoxicity, long-term follow-up care needs to continue to focus on mental health and wellness.

ICANS – A Common Toxicity

ICANS is the second-most commonly observed toxicity after CAR T-cell treatment (after CRS), and usually starts at five to 10 days post-infusion, but delayed onset after three weeks has been described in up to 10% of patients.10

Symptoms

ICANS can present with a diverse spectrum of symptoms, however many patients have a stereotypic evolution initially involving:

Tremors

Dysgraphia

Expressive aphasia

Impaired attention

Apraxia

Mild lethargy

Across multiple studies, expressive aphasia appears to be a highly specific symptom of ICANS.11,12

Patients can have rapid progression and deterioration to:13

Global aphasia

Delirium

Seizures

Cerebral oedema

Weakness

Coma in severe cases

Management

Patients with suspicion of delayed ICANS need to be referred urgently back to the hospital and specialist care for specific management.

7. SECONDARY MALIGNANCIES

While more studies are needed to evaluate the risk of secondary malignancies after CAR T-cell therapy, a small retrospective analysis of 86 patients at a median follow-up of 28 months post-treatment found that 15% of patients developed subsequent malignancy. These included non-melanoma skin cancer, myelodysplastic syndrome, melanoma, noninvasive bladder cancer and multiple myeloma.7

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency have stipulated that CAR T-cell recipients need to be followed up for 15 years following treatment to capture these events.

KEY TAKEAWAYS FOR GPs |

|---|

|

REFERENCES

Locke FL, Ghobadi A, Jacobson CA, et al. Long-term safety and activity of axicabtagene ciloleucel in refractory large B-cell lymphoma (ZUMA-1): a singlearm, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2019;20(1):31-42. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30864-7

Schuster SJ, Tam CS, Borchmann P, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of tisagenlecleucel in patients with relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphomas (JULIET): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncology. 2021;22(10):1403-1415. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00375-2

Crump M, Neelapu SS, Farooq U, et al. Outcomes in refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: results from the international SCHOLAR-1 study. Blood. 2017;130(16):1800-1808. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-03-769620

Maude SL, Laetsch TW, Buechner J, et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(5):439-448. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1709866

Hill JA, Seo SK. How I prevent infections in patients receiving CD19-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells for B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2020;136(8):925-935. doi:10.1182/blood.2019004000

Dr Ong Shin Yeu is a haematologist at Singapore General Hospital. She has a keen interest in immunotherapy for lymphoma and recently returned from a year-long fellowship at the City of Hope cancer centre in Duarte, United States of America. Back in Singapore, she contributes actively to clinical trials and research to bring immunotherapy treatment to patients.

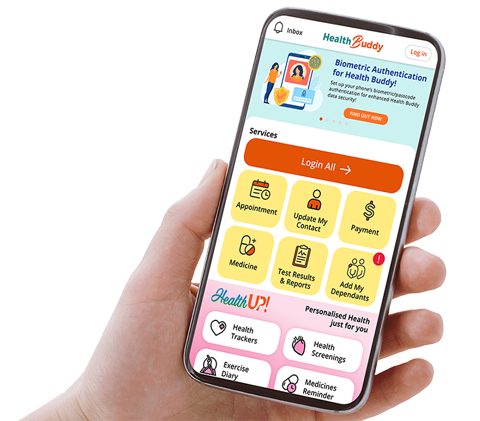

GPs can call the SingHealth Duke-NUS Blood Cancer Centre for appointments at the following hotlines, or click here to visit the website:

Singapore General Hospital: 6326 6060

Sengkang General Hospital: 6930 6000

KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital: 6692 2984

National Cancer Centre Singapore: 6436 8288