A team-based approach to primary care is key to managing the country’s chronic disease burden effectively and sustainably. In between the patients' visits to their General Practitioners, community nurses can help them make lifestyle and health improvements through health coaching and counselling techniques.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic diseases are the leading causes of death and disability globally and the increase in prevalence among Singaporeans is a cause for concern. Although the severity of the problem is well-acknowledged and lifestyle modifications are proven to manage and prevent complications, behavioural change is often easier said than done.

The didactic approach of health education has shown to be of low yield. Instead, a more powerful method known as health coaching can build a trusting relationship with patients enabling a collaborative effort to devise actionable plans to initiate and enforce behavioural change. During health coaching, motivational interviewing (MI), which is a counselling technique, is used to empower patients in moving from a passive role to actively taking charge of their lifestyle and health.

The Ministry of Health’s (MOH) Beyond Healthcare 2020 Masterplan was rolled out in 2012 to ensure affordable and sustainable healthcare for the nation beyond 2020. In line with the strategy to shift care upstream, there is tremendous emphasis on strengthening social and primary care as well as partnering general practitioners through the Primary Care Networks. GP clinics meet about 80% of the nation’s primary care demand, with a growing focus on chronic disease management. |

MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING-BASEDHEALTH COACHING

MI guiding principles used to perform health coaching can be demonstrated by the acronym RULE:

1. Resist the righting reflex

Don’t tell the patient what he knows. As healthcare practitioners, we are often instinctively quick to correct and respond to patients by giving medical advice. When a patient is ambivalent about change, telling him what he probably already knows acts as a reminder of his current health condition and may evoke feelings of being judged or blamed.

2. Understand the patient’s own motivations

Acknowledging the patient’s interests, values and concerns. This allows the practitioner to assess the patient’s readiness, willingness and ability to change. However, it is the patient’s own intention to change that ensures actualisation and sustainability.

3. Listen with empathy

Spending adequate time in communication and listening with empathy. Empathy is the ability to understand the feelings of another, and this builds trust for a therapeutic practitioner-patient relationship and encourages the sharing of more information.

4. Empower the patient

Let patients feel in control of the change. Encourage them to set their own goals and own their successes. In turn, this can lead to improved patient outcomes.

Last but not least, it is paramount that the practitioner embodies the spirit of MI by being collaborative, evocative, and respectful of the patient’s autonomy.

CASE STUDYThis case study illustrates how SingHealth Community Nurses can partner GPs and incorporate MI-based health coaching to improve a patient’s health outcomes. Background

A 70-year-old Malay male, Mr F is unemployed and lives alone in a rented flat. He has a medical history of hyperlipidaemia, chronic kidney disease secondary to hypertensive nephropathy, congestive cardiac failure, asthma with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) overlap and lumbar spondylosis. He was hospitalised almost every month in 2018 and 2019 for fluid overload. Referral to Community Nurses

Mr F was referred to the community nurses in February 2020 for high blood pressure secondary to non-compliance to medication and follow-ups. During the first visit, Mr F was guarded. Applying the principles of MI of resisting the righting reflex and listening with empathy – the nurses came across as non-threatening and receptive, allowing Mr F to open up and share more. The nurses learnt that he values his religion greatly and goes to his place of worship daily. It was important to him to stay well enough to continue to do so. He defaulted on medical follow-ups as he did not feel the need for it. The nurses invited him to share what he understood of his health condition and realised that his non-compliance was due not only to the lack of knowledge, but also to possible mild cognitive impairment which other healthcare professionals could not pick up on due to the limited time they had with him during consults. By understanding his values and motivations, the nurses were able to help Mr F set small achievable goals for himself, such as: - Taking his medication in the morning before going out

- Using a whiteboard to remind him of appointments

- Going to a nearby GP for his chronic medications instead, as he defaulted on his follow-ups at the polyclinic which was not near his home

SHARING CARE WITH GPsWith frequent coaching from the community nurses, Mr F now better understands his health condition and the related complications if it is not managed well. Nurses provided feedback on Mr F’s condition to the GP, and linked him up with a medication packing service and a social service organisation to support him in the community. Mr F’s compliance with medications and outpatient follow-ups has increased, and he does not need to be hospitalised as frequently. This case study illustrates one of the many challenges to chronic disease management. While MI-based health coaching is able to facilitate small but significant improvements to an individual’s lifestyle and health, GPs might find it challenging to do so during the short consultation time with patients. A team-based approach of bringing together various community partners to care for patients can make the change more feasible and sustainable. |

Partnering GPs to Care for Residents in the Community:

The SingHealth Community Nursing Programme

The SingHealth Community Nursing Programme is led by a team of registered nurses, trained in specialties such as chronic disease management, gerontology, oncology or palliative care. They run Community Nurse Posts (CNPs) which are located in various Senior Activity and Family Service Centres, religious organisations and even Residents’ Committees. This allows the nurses to be in close proximity to residents with multiple comorbidities and chronic diseases.

Apart from seeing them in the CNPs, the nurses also conduct home visits to residents who have difficulty going to the CNPs or require home assessment. By leveraging technology such as video consultations and vital signs monitoring, residents are able to manage their health in the comfort of their own homes.

The nurses’ frequent interaction with residents puts them in a good position to build relationships and apply MI-based health coaching techniques in managing residents’ chronic conditions.

To ensure that care is coordinated for each resident, the community nurses form the bridge between the different care providers, such as the specialists, GPs and physicians from polyclinics, maintaining an open feedback loop with all parties.

WHO AND HOW GPs CAN REFER

Do your patients have the following issues?

- Poorly controlled chronic diseases

- Lack of knowledge of their health conditions

- Problems with medication compliance and self-management

- Requiring support at home after discharge from the hospital

Consider referring them to the SingHealth Community Nursing Programme if they are:

- 60 years old and above

- A Singaporean or Permanent Resident

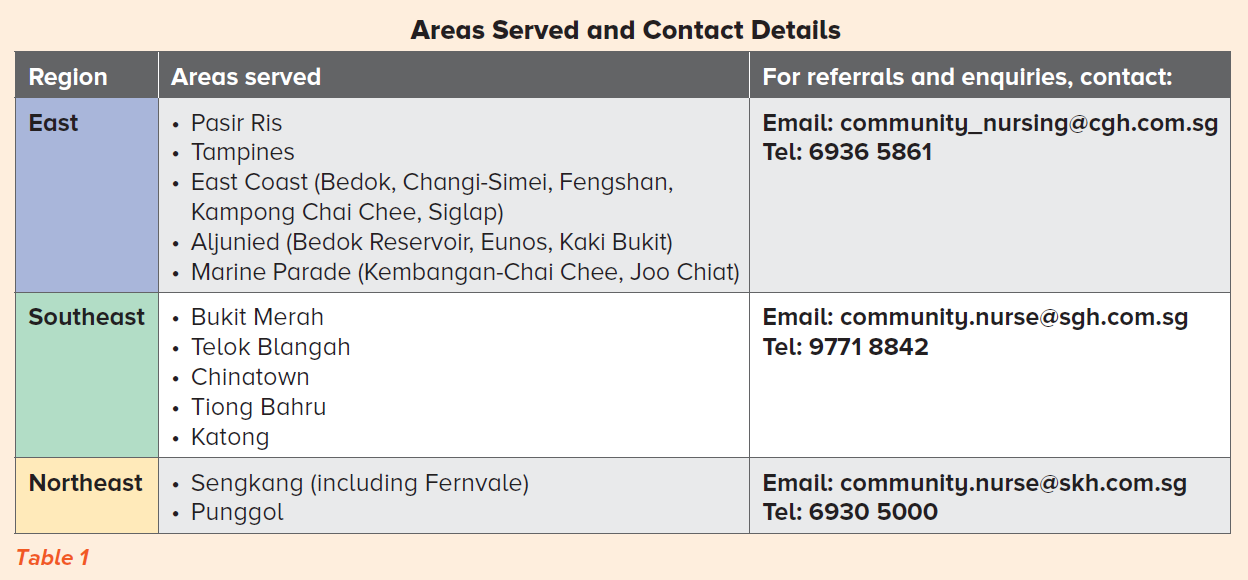

- Residing within the areas listed (Table 1)

If your patients do not meet the above criteria but may benefit from our programme, we can review them on a case-by-case basis.

Services provided:

Health and geriatric assessment

Health coaching for disease prevention

Chronic disease monitoring

Education on self-care, medication and chronic disease management

Medication consolidation

Caregiver training

Care coordination with community health and social care agencies

A community nurse will respond to the referral source and maintain open communication with the GP via phone call, email or memo. The patient’s progress will be fed back to the referring doctor when there are changes in his/her medical condition.

For more details or to download the referral form, please visit:

https://www.singhealth.com.sg/rhs/live-well/Community-Nursing

REFERENCES

Felicia, C. (2019). Over-60s suffering more with chronic diseases than a decade ago: Study. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/over-60s-suffering-more-with-chronic-diseases-than-a-decade-ago-study

Gan, K. Y. (2017). Futurehealth 2017, Innovations Transforming Healthcare [Speech transcript]. Retrieved from https://www.mti.gov.sg/-/media/MTI/ITM/Essential-Domestic-Services/Healthcare/Healthcare-ITM---Speech.pdf

Hall, K., Gibbie, T., & Lubman, D. I. (2012). Motivational interviewing techniques: Facilitating behaviour change in the general practice setting. Australian Family Physician, 41(9), 661-667.

Laverack, G. (2017). The Challenge of Behaviour Change and Health Promotion. Challenges, 8(25), 1-4. Doi: 10.3390/challe8020025

Ministry of Health of Singapore. (2020). Primary Healthcare Services. Retrieved from https://www.moh.gov.sg/home/our-healthcare-system/healthcare-services-and-facilities/primary-healthcare-services

Simmons, L. A., & Wolever, R. Q. (2013). Integrative Health Coaching and Motivational interviewing: Synergistic Approaches to Behavior Change in Healthcare. Glob Adv Health Med, 2(4), 28-35. Doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2013.037.

Sobell, L. C., @ Sobell, M. B. (2008). Motivational Interviewing Strategies and Techniques: Rationales and Examples. Retrieved from: http://www.nova.edu/gsc/forms/mi_rationale_techniques.pdf1

Vallis, M., Lee-Baggley, D., Sampalli, T., Shepard, D., McIssaac, L., Ryer, A., Ryan-Carson, S., & Manley, S. (2019). Integrating behaviour change counselling into chronic disease management: a square peg in a round hole? A system-level exploration in primary health care. Public Health, 175(2019), 43-55. Doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.06.009

World Health Organization. (2005). Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment: WHO global report. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/full_report.pdf

Xu, Y., & Lim, S. F. (2019). The Development of Geographically-Based SGH Community Nursing in SingHealth (Southeast) Regional Health System.The College Mirror, 45(1), 12-13.

Ms Ng Xiang Ling is a Senior Staff Nurse in Community Nursing, Singapore General Hospital. She was awarded the Specialist Diploma in Community Gerontology Nursing and Bachelor of Sciences (Nursing) from Edinburgh Napier University. She has seven years of nursing experience.

Ms Tay Priscilla is a Senior Staff Nurse in Community Nursing, Changi General Hospital. She was awarded a Bachelor of Nursing (University of Adelaide) and Advanced Diploma in Nursing (Medical-Surgical). Her 12 years of nursing experience include working in the acute medical ward and in Nursing Education as a Clinical Instructor.

Tags:

;

;

;

;

News Article;

Singapore General Hospital;Changi General Hospital;

Singapore General Hospital;Changi General Hospital;

Article;

Defining Med;Medical News;

;

;

;

;

Defining Med;Medical News (SingHealth);Patient Care