Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, if untreated, can cause much distress to both the patient and caregiver. Through a collaborative, person-centred approach working with caregivers and community agencies, GPs can help to recognise and manage these symptoms with appropriate psychosocial interventions and medications if needed.

INTRODUCTION

With rapid population ageing, we will see a significant increase in the number of older adults living with Alzheimer’s dementia and other dementias. Locally, the Well-being of the Singapore Elderly (WiSE) Study (2015) found that one in ten seniors aged 60 and above has dementia.1 From 80,000 Singaporeans with dementia in 2017, the numbers are expected to more than double to 150,000 in 2030.

WHAT IS BPSD?

Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) is an umbrella term that encompasses a wide range of non-cognitive symptoms that can cause significant distress and disability if untreated.

As the number of persons with dementia (PWD) grows, it is imperative for us to recognise these symptoms and provide appropriate management approaches to improve quality of life for PWD and their caregivers.

PREVALENCE AND IMPACT

80% of PWD experience at least one symptom of BPSD from the time of onset of their cognitive symptoms.2

In addition to the emotional distress and disability patients experience due to BPSD, it is also associated with increased caregiver stress, increased hospitalisations, and substantial increases in financial costs and premature institutionalisation.3

SYMPTOMS

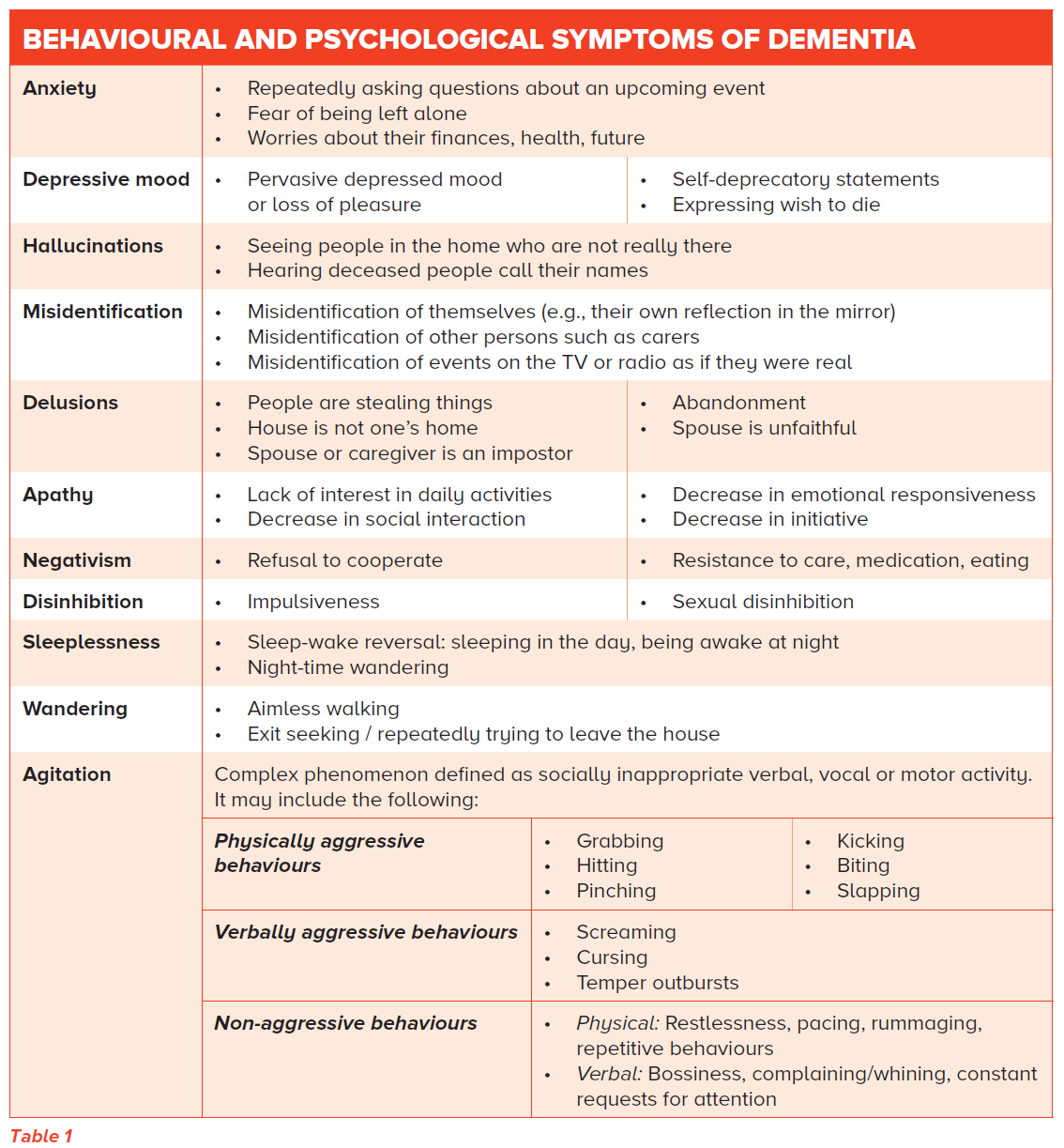

BPSD can occur at any stage of dementia. Some symptoms are more commonly seen in certain types of dementia, although there are contradictory findings in the literature.

Examples include:

Depression has a strong relationship with vascular dementia

Visual hallucinations are more common in Lewy body dementia

Impulsivity and sexual disinhibition are more frequently observed in patients with frontotemporal dementia

An overview of the different behavioural and psychological symptoms is described in Table 1.

A commonly described phenomena is sundowning, where BPSD such as agitation worsens in the afternoon or evening. Sundowning increases the levels of caregiver stress and burden, as evenings are typically the time when loved ones return from work or when there are fewer staff on duty in nursing homes.

Beyond daily variations in severity of BPSD, the nature and severity of BPSD also changes with time as the dementia progresses.

Management Approach for BPSD

1. IDENTIFY UNDERLYING MEDICAL CAUSES

An important differential to consider when addressing behavioural change in PWD is delirium.

PWD usually have multiple medical comorbidities and are particularly susceptible to biological and environmental stressors that can easily tip them into delirium.

As such, it is important to rule out common causes such as infections (e.g., pneumonia, urinary tract infections), constipation (faecal impaction), pain, prescription (e.g., opioids, antihistamines) and nonprescription medication side effects.

2. BEHAVIOURAL OR PSYCHOSOCIAL APPROACHES

Behavioural or psychosocial approaches are the mainstay of treatment for BPSD and should always be considered first over pharmacological options.

MANAGE SOCIAL AND PHYSICAL TRIGGERS

According to the unmet needs theory, BPSD stems from our need for meaningful activity, emotional validation and social interaction.4

Many behavioural symptoms result from unmet needs based on social and environmental factors such as social isolation, the need for touch or intimacy, the need for privacy during personal care, environmental noise and temperature.

Other common triggers include physical or verbal limitations leading to an inability to express needs (e.g., hunger, pain, toileting needs), physical or emotional distress, the inability to move, sensory impairments (vision, hearing) and skin problems (dryness, itching, pressure sores). These factors should be routinely checked for and addressed.

Once we understand the circumstances that trigger behaviours and what makes them better or worse, we can intervene through a variety of strategies that include communication, distraction and environmental changes.

Some techniques are described below:

Communication

Speak slowly and use appropriate eye contact, body language and tone of voice.

Use simple and direct statements.

Allow choice wherever possible and avoid patronising talk.

Do not shout/argue – there is no need to focus on who is right or wrong. Arguing usually makes the situation worse.

Encourage them to talk about how they are feeling.

Distraction

Talk about pleasant memories.

Defuse the situation by shifting their focus to a different activity, or moving to a different space.

Environment

Reduce clutter in the home.

Ensure a large clock and calendar are easily visible; ensure there is a night light; label cabinets and drawers.

Remove dangerous objects from the home or restrict access to them.

Install grab bars and anti-slip mats.

Avoid reflective surfaces.

Avoid relocation but if really necessary, bring familiar items along.

Apply for the Alzheimer’s Disease Association’s (ADA) Safe Return Card; download the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) Dementia Friends mobile application.

INITIATE PSYCHOSOCIAL INTERVENTIONS

There are a variety of psychosocial interventions including music therapy, reminiscence therapy, aromatherapy, pet therapy and multisensory stimulation.6

Effective activities are meaningful, tap on PWD’s past skills and interests and are able to provide them with a sense of normalcy. It is important to encourage caregivers to focus on the process and not the result.

LEVERAGE ON DEMENTIA DAY CARE AND ELDERSITTERS

A referral to a dementia day care centre (via AIC) to meaningfully engage PWD can also be considered. Some PWD may be reluctant to attend initially, but once the routine has been established, many derive significant enjoyment from the activities and often look forward to day care.

Eldersitters are an alternative if dementia day care is not a feasible arrangement for some families.

EDUCATE AND SUPPORT CAREGIVERS

Educate caregivers

It is important to educate caregivers on how behaviours are caused by the disease and not an intentional act.

The adjustments in communication style, routines and environment have to be borne by caregivers. It can be helpful to show caregivers pictures of brain shrinkage caused by dementia compared to that of a healthy brain, to help them frame the behavioural symptoms in the right context.

We should encourage caregivers to see beyond the illness, to recognise PWD as individuals, remembering the person they were before the illness, and take into account individual likes, dislikes, hobbies and sources of fulfilment to structure their day-to-day care and routine. This person-centred approach5 makes all the difference in the experience of both the patient and caregivers.

Caregiver self-care

Caregivers of PWD spend a disproportionate amount of time on their caregiving roles and are at risk of caregiver stress and burnout. Reminding caregivers to practice self-care, setting aside time for their own activities, medical appointments and relaxation, is important.

Support groups

The ADA and Caregivers Alliance run caregiver training and support groups. Community programmes such as Family of Wisdom (ADA) and Club Memorable (Apex Harmony Lodge) are unique care concepts available. Respite services are also available through various providers in situations where carers need help unexpectedly.

The AIC’s Go Respite programme allows carers to plan ahead for such situations.

3. PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS

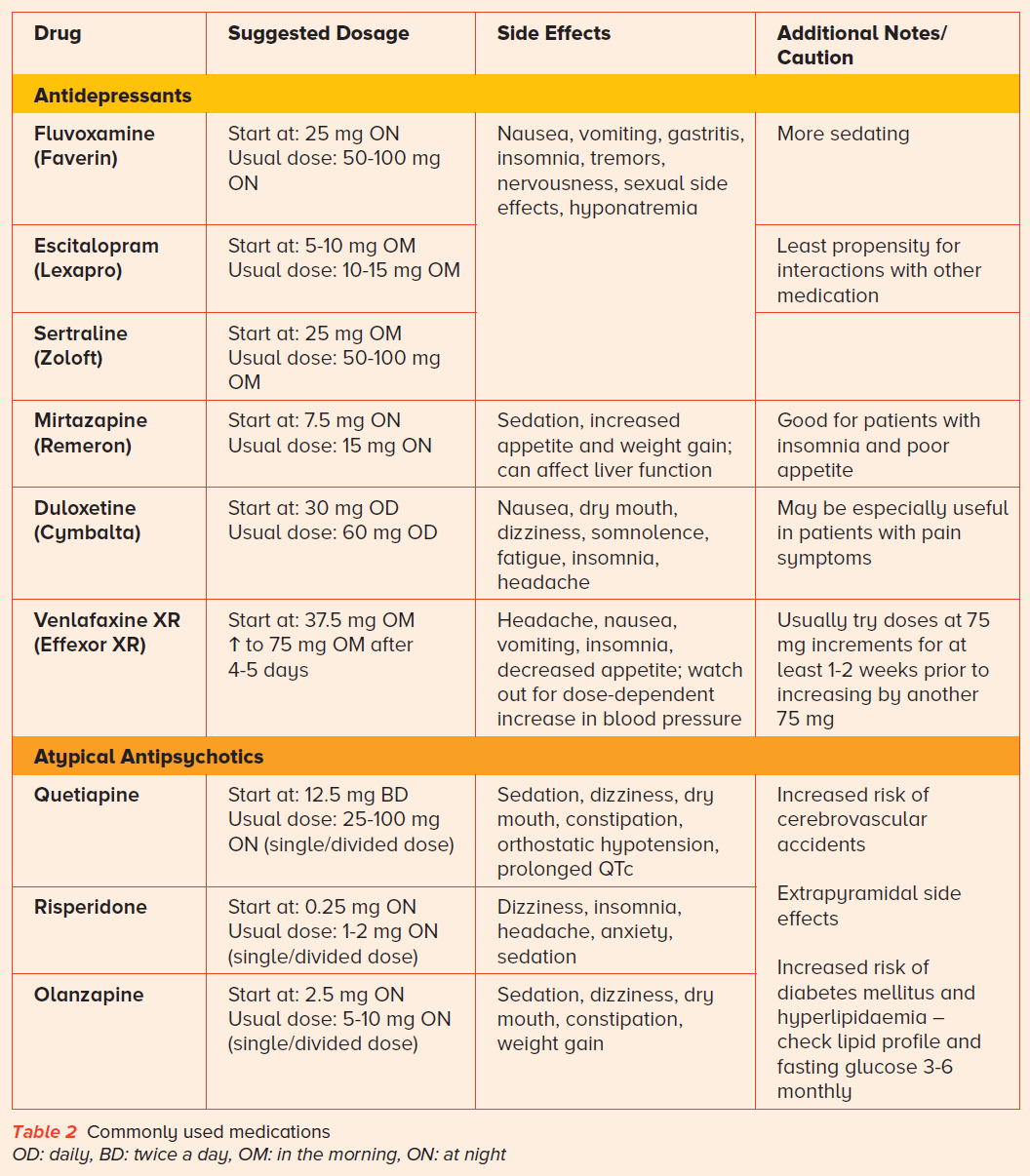

Medications should be considered only when non-pharmacological interventions have failed, or when the symptoms are moderate to severe and have an adverse impact on the PWD or caregiver.

Antidepressants and antipsychotics can be used sparingly (Table 2) and in accordance with the Ministry of Health (MOH) Clinical Practice Guidelines on Dementia.

Both atypical and typical antipsychotics confer an increased risk of mortality and stroke in patients with dementia. Melatonin and low doses of trazodone (25-50 mg at night) can be considered for sleep problems.

General principles include using lower doses (half to a quarter of the adult dose), targeting specific behaviours, using one drug at a time, regularly reviewing medication effects and ensuring use is time-limited.

| If there is a failure to respond to appropriate psychosocial interventions or a first trial of medication, or there are concerns about risks, we recommend referring to a psychogeriatrician. |

CONCLUSION

Ultimately, every PWD is different and there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ strategy. However, taking the approach outlined and working collaboratively with caregivers and community agencies to adopt a person-centred approach can go a long way toward maintaining independence and quality of life for PWD.

REFERENCES

- Subramaniam M, Chong SA, Vaingankar JA, Abdin E, Chua BY, Chua HC, et al. Prevalence of dementia in people aged 60 years and above: results from the WiSE study. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2015;45(4):1127-38.

- Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. Jama. 2002;288(12):1475-83.

- Finkel SI. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD): a current focus for clinicians, researchers, caregivers, and governmental agencies. Contemporary neuropsychiatry. 2001:200-10.

- Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: a review, summary, and critique. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2001;9(4):361-81.

- Kitwood TM. Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first: Open university press; 1997.

- Ministry of Health, Singapore. Dementia MOH Clinical Practice Guidelines 1/2013 [online]. Available at: https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider4/guidelines/dementia-10-jul-2013---booklet.pdf

Dr Iris Rawtaer is a Psychogeriatrician at Sengkang General Hospital, a clinical site of the SingHealth Duke NUS Memory & Cognitive Disorder Centre. She has a keen interest in neurocognitive disorders and mental health of older adults. She is involved in epidemiological and interventional studies of ageing and has been working on remote sensing technology for early detection of dementia.

GPs can call the SingHealth Duke-NUS Memory & Cognitive Disorder Centre for appointments at the following hotlines:

Singapore General Hospital: 6326 6060

Changi General Hospital: 6788 3003

Sengkang General Hospital: 6930 6000

National Neuroscience Institute: 6330 6363